The Wicked Bible

by Chris Jones

What is the Wicked Bible?

The story of the Wicked Bible begins not, as one might assume, in the turbulent years of the 17th century leading up to the English Civil War, but at a lecture given in 1855 at the Society of Antiquaries of London. It was here that an American book dealer, Henry Stevens, announced the discovery of what, up until then, was widely assumed to be a myth: a bible whose seventh commandment read ‘Thou shalt commit adultery’ (Exodus 20:14). In the course of his lecture, Stevens gave his new discovery the name that has stuck: he called it the ‘Wicked’ Bible.

The copy Stevens displayed in London, and which is today in the New York Public Library, had been discovered in Holland. We do not know the name of the book dealer who found it but it was once part of the library of John Canne, a non-conformist English minister who worked as a printer in 17th-century Amsterdam.

When Stevens borrowed the Canne Bible to assess it, he was able to identify three key features: the year of publication (1631); the printer (Robert Barker, the King’s Printer); and the format (octavo, which is roughly the size of a modern paperback). Armed with this information, book dealers and scholars were now able to begin searching for what became a latter-day holy grail. The first discovery based on the new information was made by Stevens himself: to his surprise, he found he already owned a copy, a stroke of good fortune that enabled him to secure a 50% discount from the luckless book dealer selling Canne’s copy. Although Stevens’s second copy was incomplete, he sold it to the British Museum where it later became the British Library copy.

Until 2022 it was generally assumed that fewer than ten Wicked Bibles survived, one of which was thought to be in Australia. We now know that the Australian copy is a mis-identification but that at least twenty-five copies remain extant, eighteen of which are held in institutional collections around the globe. Most are found in the United Kingdom and the United States. However, in addition to the Donnithorne-Christchurch copy in Aotearoa New Zealand, copies can be found in Canada, Ireland and in Italy. In fact the copy in Rome was discovered in February 2023 by Quillan Taylor while working on the Wicked Bible Project website: this copy had been made available online in 2013 by Google Books but its most distinctive feature had been overlooked.

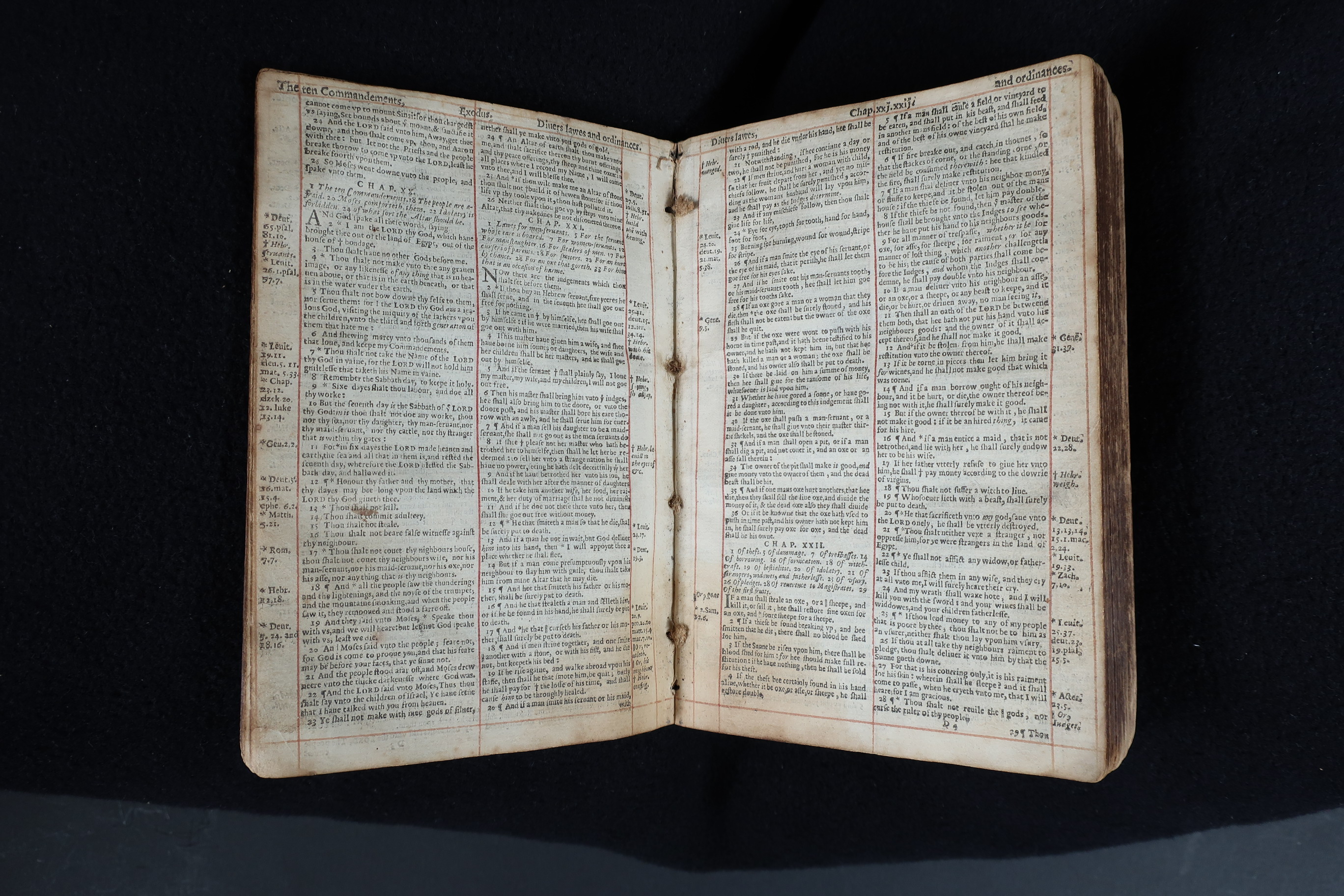

Work undertaken in connection with the Wicked Bible Project has also uncovered new evidence for a second significant printing error. This error has sometimes been dismissed as a myth because it does not occur in any of the known Wicked Bibles in the British Isles. However, it appears in three North American copies alongside the missing ‘not’. These include the unique, uncorrected copy in the Dunham Bible Museum, Houston. In this, the ‘Wickedest’ Bible, the Book of Deuteronomy suggests the Lord ‘hath shewed us his glory, and his great asse,’ rather than His ‘greatnesse’.

Why is there a Wicked Bible in Aotearoa New Zealand?

A copy of the Wicked Bible has been owned since 2016 by The Phil and Louise Donnithorne Family Trust based in Christchurch, New Zealand.

The bible first entered modern records amongst the effects of Don Hampshire, a Christchurch book binder who died in December 2009. How – and when – Hampshire came by his copy we simply do not know. Nor do we know if he knew what it was that he had. He may have brought it with him from his native England when he emigrated after World War II; equally, he may have acquired it in New Zealand.

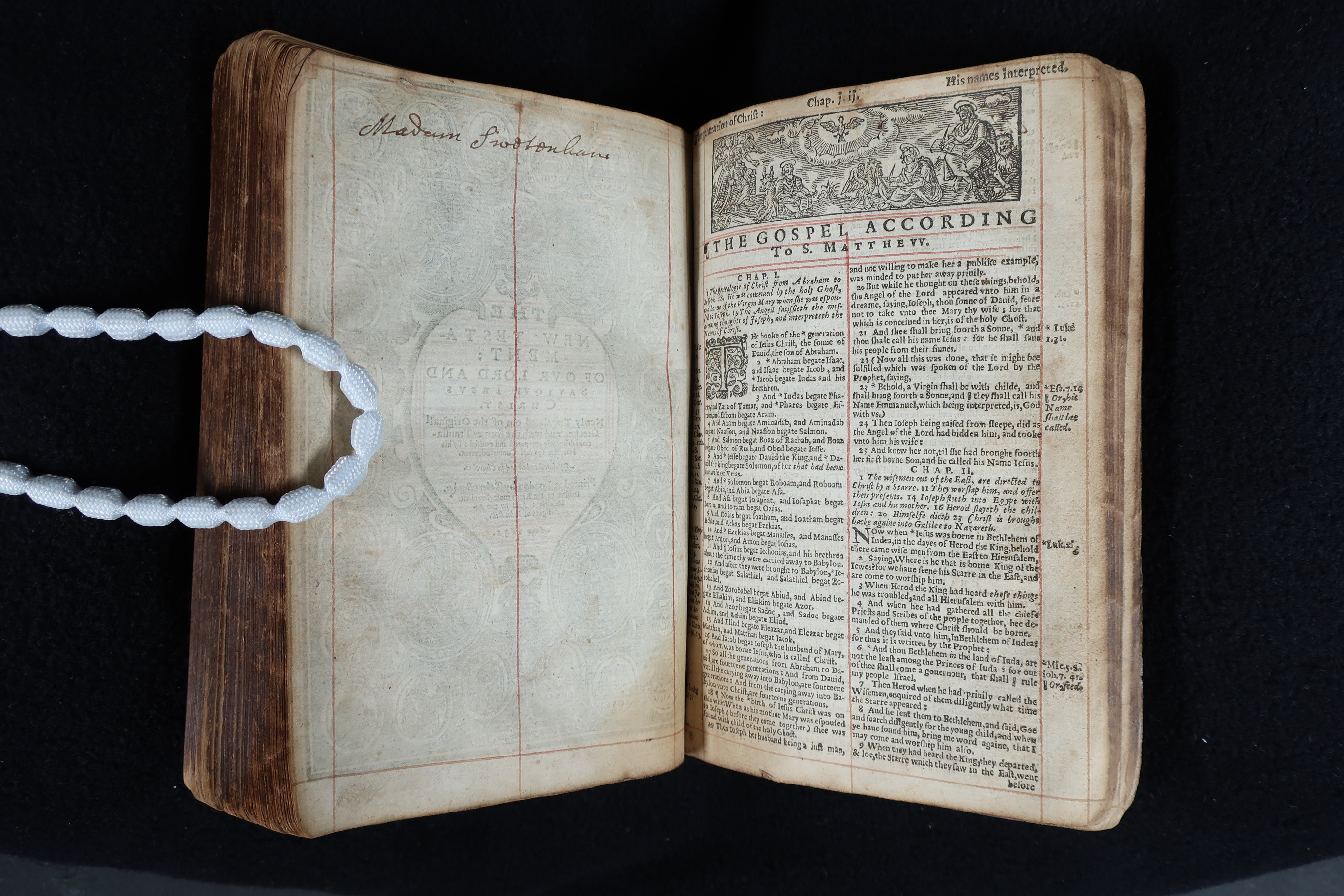

When the book was found it had been stripped of its boards and original end sheets, which might have contained traces of its origins. The only sign of the book’s earlier provenance is the name ‘Madam Swetenham,’ which appears written in ink on a blank page following the New Testament title page. As yet, we do not know who she was. The early history of the Donnithorne-Christchurch copy is a mystery deserving of further investigation.

Myth and reality, or why ‘not’?

Myths surrounding the Wicked Bible have proliferated in the age of the internet. One of the most persistent, which originates with Stevens himself, is that all the copies were ordered destroyed. We know that this was, without doubt, not the case. A key aim of the Wicked Bible Project is to conduct research in an area where remarkably little has been undertaken, partly in order to separate myth from reality.

Another oft-repeated ‘fact’ – that the missing ‘not’ was the result of industrial sabotage – originates in a theory first aired in the late 1950s. The bible’s printer, Robert Barker, was certainly involved in long-running disputes with several of his fellow printers. However, there is very little evidence to suggest the errors of the Wicked Bible, even its most famous one, result from sabotage. Even Barker did not think his competitors had gone this far. We know this – as we know the fate of the books – from the records of a court case.

The errors in the 1631 printing saw Barker brought before the court of High Commission, which policed religious printing. This, it should be noted, is despite another persistent modern myth that the case was tried in the infamous court of Star Chamber. The High Commission upbraided Barker for his choice of poor paper, unwillingness to employ qualified correctors and general lack of quality control. Barker could only shrug and attempt to shift the blame: it was, he claimed, ‘being the fault of the workemen’. The end result was a modest fine.

The court agreed that the impounded books should be handed back to the printers, albeit with a requirement that they be corrected before being resold. Some of the 25 copies known today, including the Donnithorne-Christchurch copy, contain evidence of remarkably similar attempts to correct the errors in Exodus or Deuteronomy. These may be signs of the printers’ efforts to comply with the court order. There is, in any case, little indication that the affair damaged Barker’s reputation. And even his relatively small fine was waived in return for an agreement to work on a new project for the king.

What can we learn from the Wicked Bible?

The work of the much-neglected court of High Commission is the subject of a new evaluation by Annika Stedman as part of the Wicked Bible Project. What powers did this court exercise in post-Reformation England? How did it shape peoples’ lives? By studying the Wicked Bible itself we can also learn much about the way in which religious books were employed in 17th-century English society. The Wicked Bible can also open a door onto the world of printers, book production and the book trade more generally.

Evident in the Donnithorne-Christchurch copy is a tendency to sell bibles alongside additional texts. These composite – or anthology – volumes can tell us about how the bible was read but also about how the book trade operated. Barker and his team seem to have collaborated with other printer-publishers to offer their customers a series of ‘set’ options. Customers were given a degree of choice, perhaps tailored not simply to individual tastes but to individual budgets. It is difficult not to see similarities with the tendency of modern car dealerships to offer their customers pre-set packages of upgrades!

Books were often bound in a specific order. The most common surviving combination consists of: a Book of Common Prayer; a copy of John Speed’s 1631 Genealogies with a map of Canaan; the bible itself; and a book of Psalms. This Wicked Bible composite can now be found at the University of Leicester, the John Rylands Library, Manchester, and the Biblioteca nazionale centrale di Roma. The Donnithorne-Christchurch Bible is, however, preceded only by Speed’s Genealogies. In common with several other copies, these appear without the added luxury of a map. However, in the Donnithorne-Christchurch copy, the bible is followed not only by the psalms but by a concordance. The latter was a valuable tool for someone who planned to make use of the text, as opposed to, for example, someone who purchased their bible as a luxury product or to make a statement about their religious loyalties.

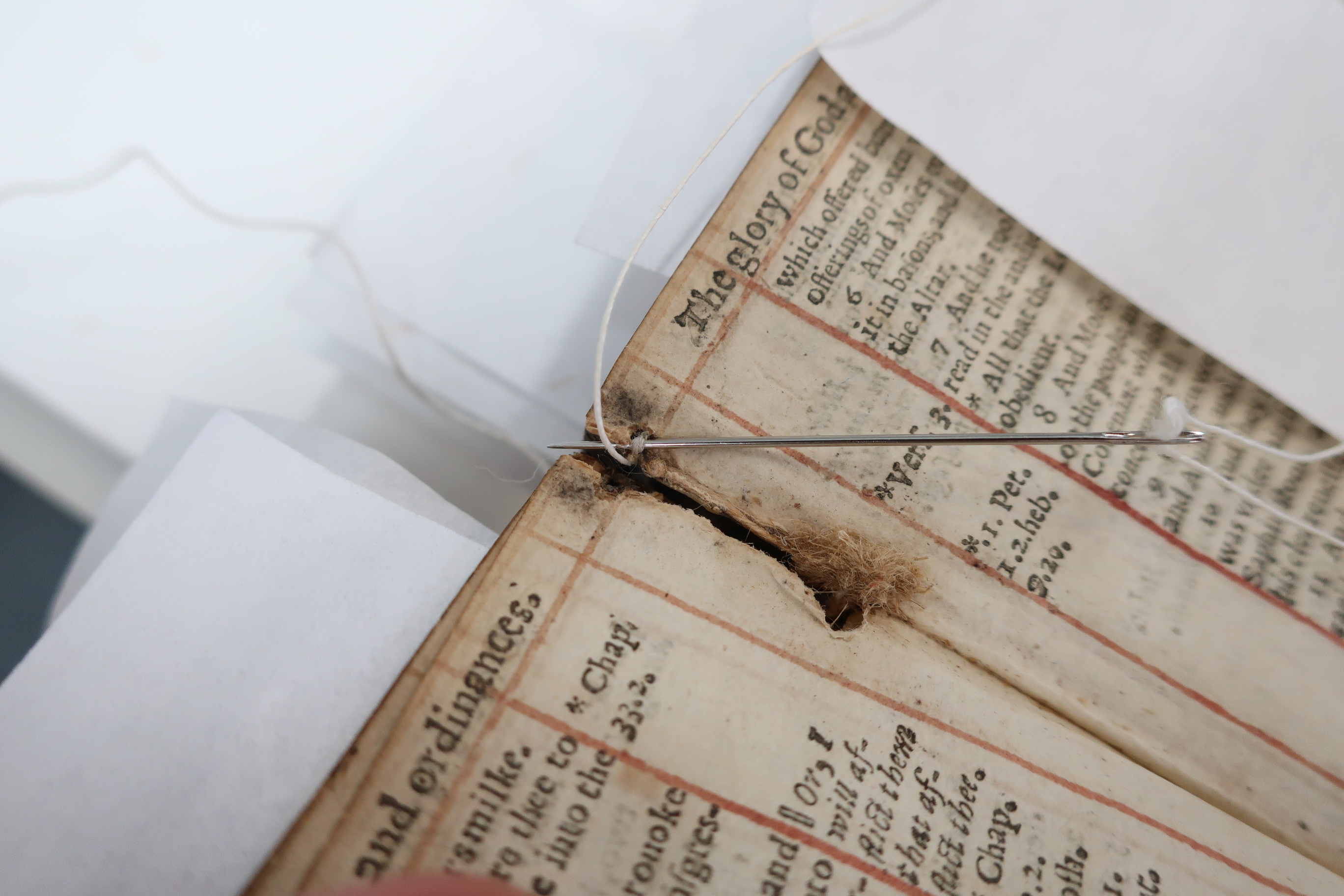

Another aspect of the production process is tied to one of the Donnithorne-Christchurch copy’s most striking features: its use of red-lining as decoration. How was this achieved technically? Was it another part of the printer-publishers’ efforts to cater to individual preferences? This is the subject of Quillan Taylor’s research available elsewhere on this site.

Future research

Since 2018 the Donnithorne-Christchurch Bible has been on long-term loan to the Macmillan Brown Library at the University of Canterbury. The generosity of The Phil and Louise Donnithorne Family Trust has meant that scholars now have a unique opportunity to examine this volume.

In 2021 a conservation project was carried out by the independent book and paper conservator Sarah Askey to stabilise and protect the bookblock. Since that time, David Moseley has completed the first substantial modern research on the Wicked Bible. His MA dissertation, ‘“Not” Funny? Humour, Embarrassment, and the “Wicked Bible”’, available via the UC Research Repository, offers new insights into how the English language’s most famous typographical error was perceived by contemporaries.

Going forward, the Wicked Bible Project offers a platform to enable further student-led investigation of the text, as well as publishing and printing and the wider history of 17th-century English society.