The Court of High Commission

by Annika Stedman

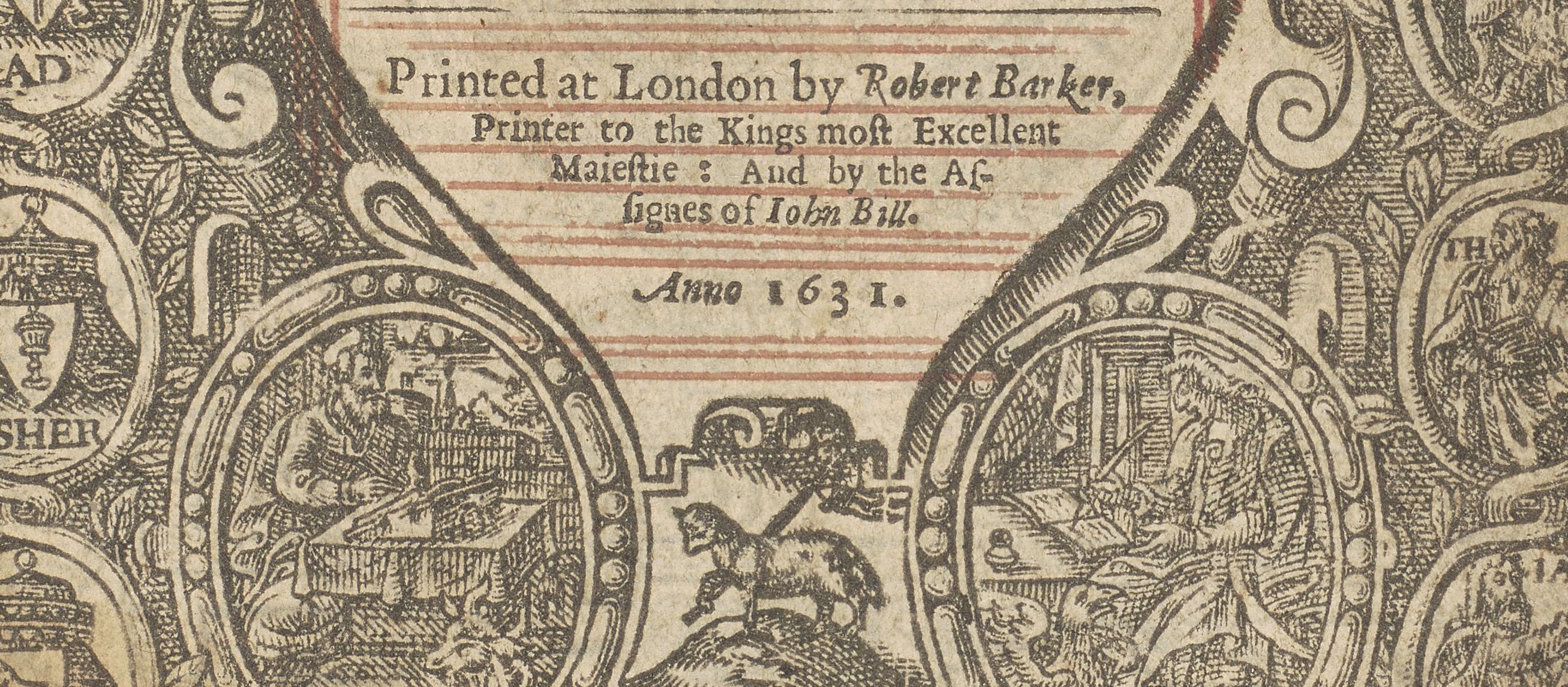

In early 1631 reports began to pour in of a new and highly scandalous mistake in a particular print run of bibles. The discovery of such a ‘wicked’ error eventually led to the printers – Robert Barker and Martin Lucas – being taken to court. After all, they were the official King’s Printers; not only did they hold the royal patent to print the Holy Bible of King James, but they also held a monopoly on the printing and sale of bibles in England. This monopoly was one that had been vigorously – though not always effectively – enforced on their behalf, and, as such, they were expected to provide a steady stream of high quality, English-made bibles to supply the English people.

The omission of the word ‘not’ from the seventh commandment – which now read ‘Thou shalt commit adultery’ – was not the only complaint that was levelled against the printers. Almost all the bibles to come out of their print shop were riddled with mistakes and defects. The printing was done fast and cheap in an attempt to compete with the stream of low-cost Geneva bibles that were being smuggled into England to be sold for profit. The paper was low-quality, the ink often smudged and portions of the bibles were sometimes even leftovers from old print runs, which had to be trimmed to fit. All in all, this new ‘wicked’ error was merely the latest in a long and frustrating line of mistakes.

But where could the printers be tried? What they had done was not necessarily illegal, at least under common law. If they were hauled up in front of the court of King’s Bench on criminal charges, it was highly unlikely anything would come of it. It has sometimes been wrongly stated that they were instead tried in the court of Star Chamber – a court which usually dealt with serious cases of political dissent, heresy or treason. However, this was not the case. It was evident to most involved that the error had occurred out of negligence rather than a heretical desire to promote extramarital activities. In fact, the omission of the word ‘not’ was such a common printing error that the legal system in England had begun to use the terms ‘guilty’ and ‘innocent’ instead of ‘guilty’ and ‘not guilty’ to avoid the confusion and legal ramifications of an accidentally misprinted verdict.

The court of High Commission

The court of High Commission went through various iterations before becoming an official, independent body in the 1580s. Its powers were initially limited, and focussed primarily on dealing with Roman Catholics and enforcing religious conformity under the reign of Elizabeth I in the mid-16th century. By the 1630s, its reach had expanded. Using somewhat outdated articles established under the first act of Elizabeth’s reign, the court’s jurisdiction extended from printing, marriage and the regulation of the teaching in churches, to any other outrageous misbehaviours. The lack of clear legal boundaries in these articles allowed the court a high degree of freedom. As a result, one of the court’s unique features was its flexibility. The court could impose fines, imprisonment and other penalties, but it also had the power to find solutions to problems in any way it saw fit, as long as it was lawful. The courts of King’s Bench and common pleas could not do this, and had to apply common law principles.

If you were a defendant, the court of High Commission was the place you wanted to be tried in in order to get the best outcome. Lawyers fought to get their cases seen in front of the commissioners, and in the case of Robert Barker and Martin Lucas, it worked out fairly well. They were lucky enough to avoid the – potentially far more serious – consequences of being tried in Star Chamber, and instead managed to get off with a fine. A similar case was also tried in 1631 when Dr William Slater, an academic at the University of Oxford, was accused of adding rather dirty limericks to the ends of his translations of the Psalms, and then distributing printed copies. After a brief period of imprisonment at the mercy of the court, a chastened Dr Slater stated that he was ‘heartily sorry’, upon which the archbishop gave him a thorough reproof and let him go. As the poor doctor was leaving the courtroom he was called back by the bishop of London who, apparently unable to contain himself any longer, proceeded to criticise the doctor’s clothes. He seems to have objected in particular to Slater’s decorative collar and excessively lacy ruffles, stating that if he ever saw the doctor dressed so flamboyantly again, the bishop would find a canon to – rather ominously – ‘take hould of him’.

Jurisdiction and authority

The court’s jurisdiction over a range of issues overlapped with the civil courts and other ecclesiastical courts. This often caused confusion and controversy as to what should be heard in this court and what should be heard in the ordinary ecclesiastical courts – that is, the bishops’ courts. In the case of the civil courts, much of this power struggle was caused by the commission’s controversial use of a particular procedure called ex officio – a term which essentially meant that you could be compelled to testify against yourself, and that your silence could be used against you if you refused. This procedure was highly unpopular, and would later be used as evidence of the court’s corruption.

Interestingly, the bishops’ courts often seem to have been very keen for the High Commission to take on more of their cases. One of the most significant impacts of the Reformation on the bishops’ courts was the shift in authority from the Catholic Church to the newly established Church of England. Before the Reformation, the bishops’ courts were closely tied to the Catholic Church, which meant that their rulings were often influenced by canon law and backed up by the authority of the pope.

However, with the establishment of the Church of England under Henry VIII, the bishops’ courts became subject to English law and the authority of the monarch. This meant that their jurisdiction was limited to matters that did not conflict with English law, such as matters of ritual, morality and doctrine. As the authority of the Catholic Church declined, secular courts began to assume a greater role in resolving legal disputes, including those that had been previously the exclusive prerogative of the bishops’ courts. Oftentimes, the bishops’ courts did not have enough authority or influence to compel defendants to appear. In contrast, the court of High Commission could issue letters of attachment which compelled a person to turn up, either by taking a bond that would be lost if a person failed to attend, or by actually imprisoning someone. Especially for cases which dealt with important or powerful people, a case in the court of High Commission was more likely to bring about an effective result.

This effectiveness – the ability to just get things done – became the hallmark of the court of High Commission. The lack of limitation on the commissioners’ jurisdiction – though it left them open to charges of corruption – allowed the court to fill a gap in post-Reformation society. In many ways, it could be compared to a modern Family Court in Aotearoa New Zealand. It was designed to be less punitive than the criminal courts and took on some of the roles that had been played previously by local religious courts: dealing with domestic violence issues and awarding victims financial independence, mediating unofficial ‘divorces’ and disciplining clergy who were abusing their role or teaching unorthodox doctrine. Unlike either a purely religious or purely civil court, the court of High Commission held enough secular authority to operate effectively, but had enough freedom of operation to treat defendants lightly or severely as the situation required.

The Resolution of the printers’ case

A wonderful example of this ‘problem-solving’ ability is illustrated by the case against the King’s Printers in 1631. The charge against them was for ‘high crimes and misdemeanours’, specifically the production and sale of a blasphemous and seditious publication. The King’s Printers pleaded guilty to the charges, and their defence was based on the argument that the error was a mistake and not a deliberate act of blasphemy. However, the English print industry still faced significant competition from Europe; Geneva bibles and European Protestant literature were being mass-produced at a faster and cheaper rate than England had yet been able to match. The king himself certainly did not want to put the printers out of business, but also needed to be seen both to punish such negligence and to prompt better quality work in future. As such, a fine of £300 was levied against Barker and Lucas. While this was not an insignificant amount – possibly around NZ$102,000 in modern currency – the part apportioned to Barker only represented 7% of his claimed annual income (approximately £3000; a somewhat staggering NZ$1.02m today). In the end, even this fine was forgiven by the court – but not before it was used to persuade Barker to comply with the king’s agenda.

Reference: A. Stedman, ‘Uncommon Justice: The court of High Commission in the early seventeenth century’, ed. Chris Jones (Christchurch: Canterbury University Press, 2024), https://doi.org/10.26021/15195.