Printing the Wicked Bible

by Quillan Taylor

The Donnithorne-Christchurch Wicked Bible is an anthology book, meaning it consists of four individual books in a single volume. It was published in 1631 by Robert Barker, the King’s Printer, but he only printed one of the four books: the bible itself. This was printed at the King’s Printing House located in Blackfriars, central London. Barker subcontracted the printing of the other three books to various other central London printers. The first book, The Genealogies Recorded in the Sacred Scriptures, was printed by Felix Kingston at his family printing house located in Paternoster Row. The second book, A Brief Concordance to the Bible, was printed a year earlier than the other books, in 1630, by Humphrey Lownes and Robert Young at their printing house on Bread Street Hill. The third book, The Whole Book of Psalmes, was printed by an unnamed printer from the London printers’ guild – the Companie of Stationers.

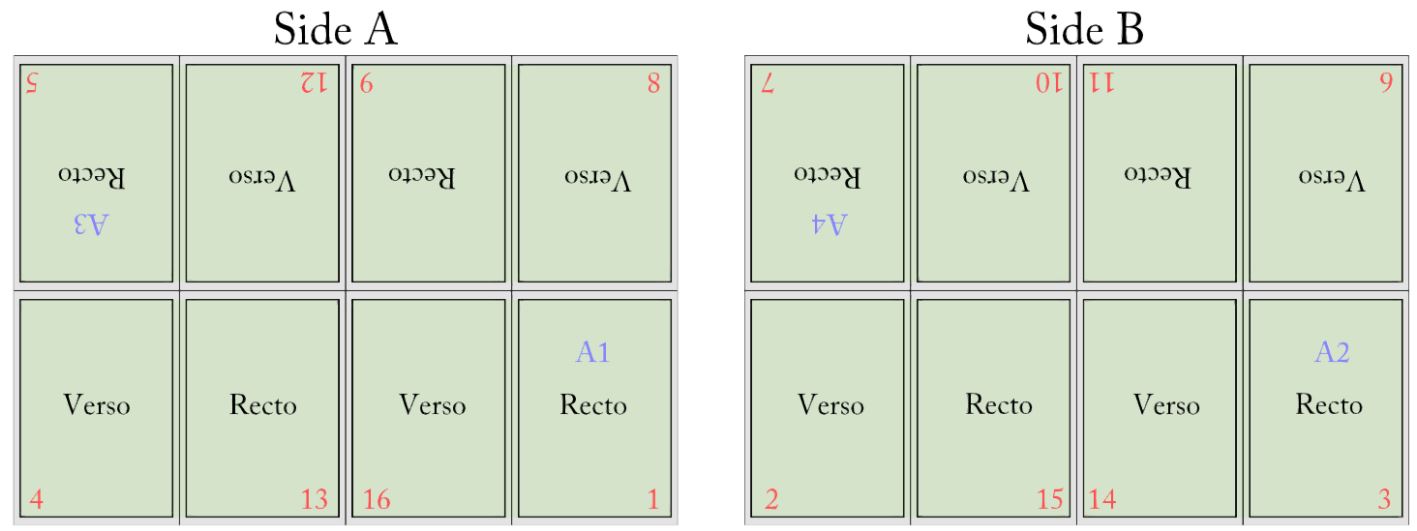

Wicked Bibles were printed in a format known as octavo. This means that sixteen pages are printed on a single print-sheet (eight on each side). These sixteen pages are grouped together in bifolios which are labelled A1 to A4, then B1 to B4 and so on.

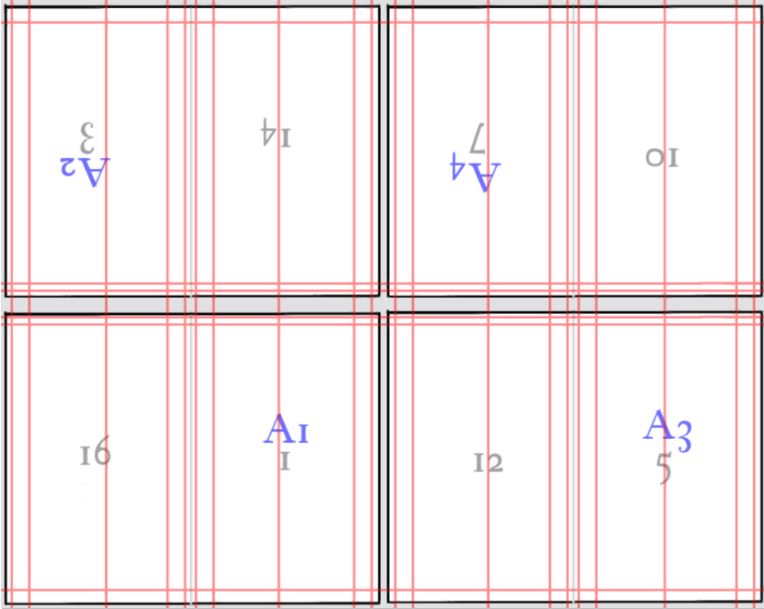

The anthology contains decorative red-ruling. The paper was probably ruled before printing as this would have been cleaner and less likely to impact legibility. Ruling after printing is difficult and requires precision to avoid smearing or disturbing the freshly printed ink. Evidence suggests that ruling in the Donnithorne-Christchurch Wicked Bible was done manually rather than by printing because the red ink used is water-based; it cannot be printer-ink, which is oil-based and not water-soluble.

The ruling was likely done with a cheap orange-red pigment known as red-lead. However, some Wicked Bibles were printed with a brilliant red pigment known as vermilion. One probable reason for half of the red-ruled Wicked Bibles being ruled in vermilion and half in red-lead is that vermilion was imported from Holland (England had no local vermilion producers). Dutch producers were highly secretive about their production methods, allowing them to include various additives in attempts to improve or dilute the colour. As a result, if vermilion stockpiles were depleted halfway through the print run, given England had no local supply and was reliant on imports, red-lead would have been the only viable substitute. Further, red-ruling was a luxury selling point for bibles, especially after their quality fell sharply during the 1620s and 1630s. Adding red-lead red-ruling was an easy way to charge luxury prices for bibles that were otherwise cheaply produced.

Printing was a process that had numerous steps. It would begin with typecasting. Movable type made printing more efficient than writing manuscripts. The process involved pouring molten metal into a mould to create small blocks with letters or characters that could be assembled to form text. Different metals were used, with alloys based in steel, iron or brass being harder, while those based in lead or copper were softer and more malleable. Typecasting required precision and specific motions to pour the metal accurately, but, once mastered, a typecaster could hand-cast an average of 4000 types per day. Typecasting was expensive, but sets could be reused for years. In 1630–31, printers may have used a softer and more malleable metal composition for printing the King James Bible. Felix Kingston, by contrast, printed text directly from woodcut engravings in addition to using metal type.

Of the forty-five printed images in this volume, thirty-three are diagrams that appear in John Speed’s Genealogies. Larger woodcuts were likely printed separately from the rest of the text. Christoffel van Sichem II, a Dutch engraver, was commissioned by Kingston for the woodcuts in Speed’s text. These are reproduction woodcuts and were likely commissioned outside of England in the Dutch Republic. This is particularly interesting as the King’s Printer was trying to challenge the illegal importation of English books produced in Dutch printing houses at this time. These woodcuts were in use for around a decade.

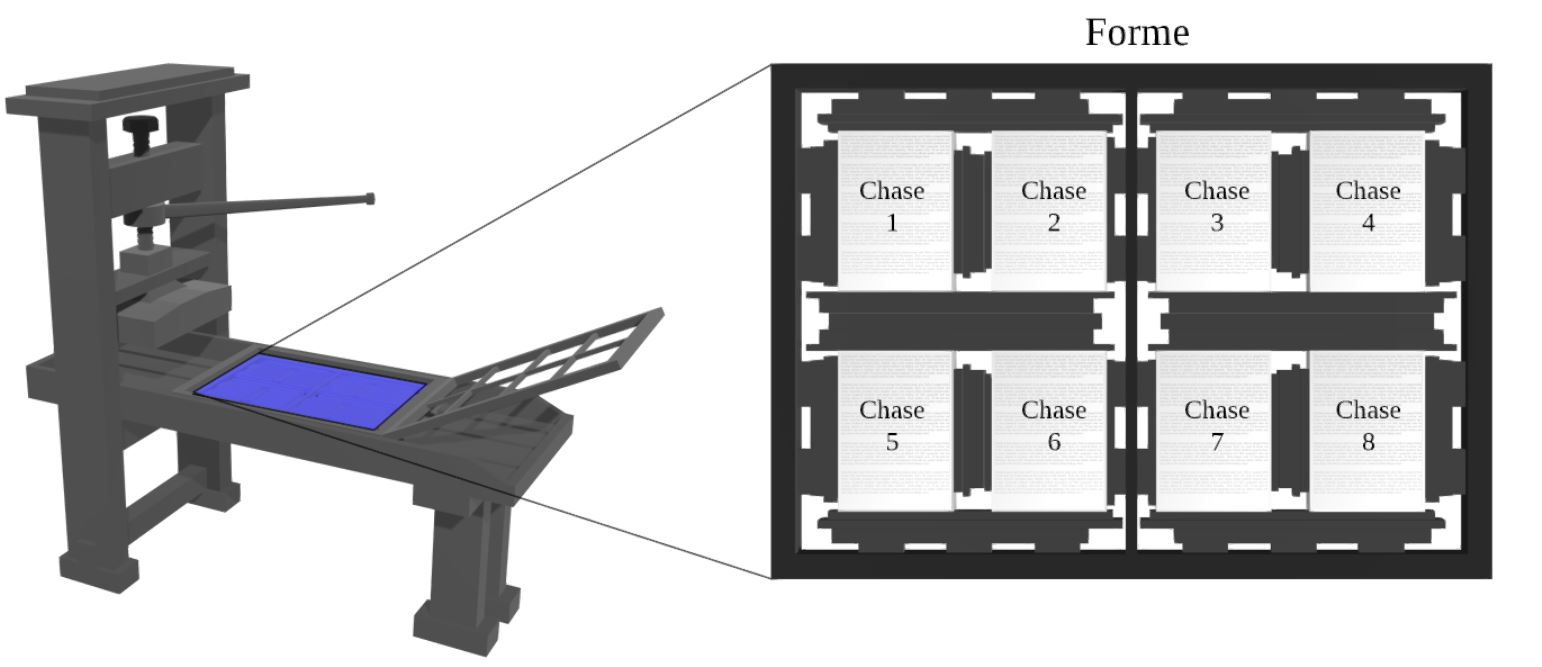

The man responsible for almost all the details of a book was the compositor. For determining the quantity of type needed for a project a compositor could employ either cast-off copy or seriatim methods. Cast-off copy printing involves examining a previously printed copy to estimate the quantity of type required, while seriatim printing involves typesetting word-by-word, line-by-line and page-by-page in a particular order. The typesetting and compositing process entails creating a forme, a frame containing the metal reliefs of eight pages (each one called a chase), each side of the print-sheet. Each chase contains the arrangement of an entire page’s type and media. A single draft sheet was printed with the forme to be checked for issues.

The poor working conditions of press workers in 17th-century London led to outcry, with a petition to the House of Commons in 1621 highlighting their exploitation by master printers. Barker’s printing house was no exception, with cost-cutting reducing staff numbers to the absolute minimum, causing strain on the remaining workers. The overworking and understaffing of proofreaders at Hunsdon House directly contributed to the famous ‘wicked’ error, the omission of the word ‘not’ in the commandment ‘Thou shalt not commit adultery’.

A printing press was typically operated by a team of two pressmen who set up and maintained the press, applied pressure to the plates and impressed the forme onto paper. Before printing, the paper was dampened to prevent damage and ensure even ink transfer. Dampening also reduced dust and debris, which could interfere with press–paper contact. Robert Barker’s printer may have skipped the step of dampening in the Wicked Bible because the red ink used for decoration is water-soluble and would have been ruined by the dampening process, resulting in less bold and smeared printing. Some smudging in this copy may indicate that the paper was sticking to the press during removal, which could be an indication of such ‘dry’ printing.

The original binding of this volume was likely a tight-back structure, but the books in the anthology were produced individually in different printing houses. They were assembled in a central location, most likely the King’s Printing House at Hunsdon House in Blackfriars, for binding. However, Barker’s financial difficulties sometimes encouraged him to skip binding his bibles altogether and to print and sell unbound or partly bound texts. This could explain why his bibles often contain an amalgamation of books from different print runs and why original bindings can vary so widely.

The Donnithorne-Christchurch Wicked Bible is a testament to cheap production methods. Barker had suffered from financial difficulties since first producing the King James Bible in 1611. His problems multiplied over the years culminating in a forced buyout by his former business partner in 1629 for £8000, a crippling financial blow that forced Barker to cut costs wherever possible; he reduced staff and used cheap materials and faster production techniques, leaving his books prone to errors and leading to the infamous error of the 1631 version.

Reference: Q. Taylor, ‘The Donnithorne-Christchurch Wicked Bible: Technical and Bibliographic Report’, The Wicked Bible Project, ed. Chris Jones (Christchurch: Canterbury University Press, 2024), https://doi.org/10.26021/15196.