The Matthew Bible (1551) (Report)

Thomas Petyt. The Byble, that is to saye, all the holye scripture : in whiche are contayned the olde and new Testament, truly and purely translated into Englishe, [and] now lately with great industry [and] diligence recognysed. Imprynted at London [1551].

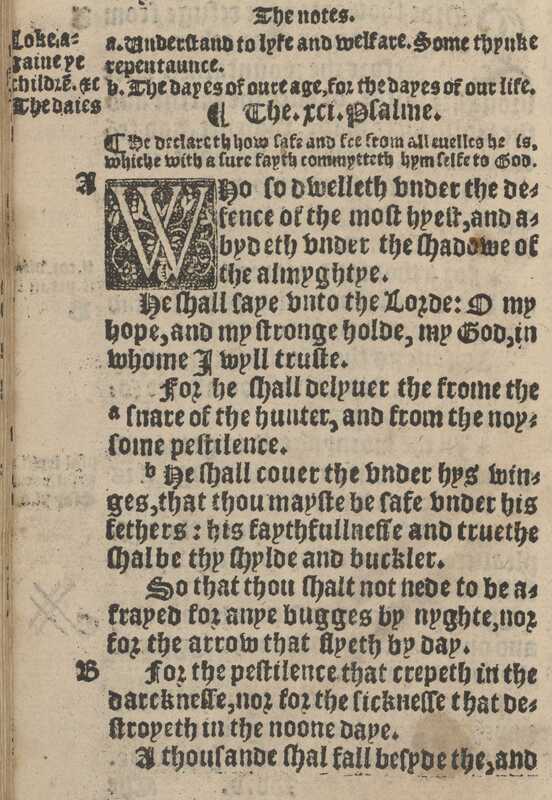

This is an edition of the bible in English, published in 1551, and based on translations by William Tyndale, Myles Coverdale and John Rogers (originally published in 1537). . This is often referred to as the ‘bug bible’ (as are earlier versions of the Matthew bible) because of the translation of Psalm 91:4, ‘thou shalt not need be afraid for any bugs by night’. This translation can also be seen in Coverdale’s 1535 edition of the bible. In the 1539 Great Bible, Coverdale replaced the word ‘bugs’ with ‘terror’, but this edition of the bible still uses the word ‘bugges’.

The Matthew bible of 1551 has a complicated pedigree, both in terms of content and its printing.

Matthew Bible, 1537:

The first edition of the ‘Matthew Bible’ was published in 1537 (see Matthew Bible 1549, a Leaf).

Taverner’s edition of the Matthew Bible, 1539:

In 1539, another edition of the Matthew bible was published. This was edited and revised by Richard Taverner, an Evangelical Reformer and Greek scholar who by 1539 was working for Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s chief minister.

By 1539, Cromwell and Archbishop Thomas Cranmer were looking to publish an official English bible for the Church of England, reflecting the King’s recent interest in Reformed (later called Protestant) ideas. Protestants believed that salvation came through faith alone (rather than the sacraments of the Catholic Church). Men, women and children could all speak directly to God through prayer. Faith came through knowledge of God, which was to be found by reading the bible. Therefore, it was important that everyone could access the bible in their own language, or in the vernacular. Previously, the Catholic church primarily used the Latin Vulgate bible, regardless of what languages people spoke.

John N. King demonstrates that Taverner was Cromwell’s ‘principal propagandist for religious reform’: he was producing English versions of Protestant texts throughout the 1530s. Cromwell employed Taverner to revise the controversial elements of the 1537 Matthew Bible, including attacks on clerical celibacy, the Catholic doctrine on purgatory, and comparisons of the Pope to the Antichrist. He also refined some of Tyndale’s translations. Taverner’s edition was soon replaced by a more thorough revision headed up by Myles Coverdale, known as the Great Bible (first edition 1539).

Two different editions of the Matthew Bible, 1549:

In 1549, two further editions were published. One was by Thomas Raynald and William Hill, printers in London, who largely reproduced the 1537 text without any significant changes.

The other 1549 edition was printed by John Day and William Serres. This edition differed from the 1537 Matthew bible in that it had new notes and was edited by Edmund Becke. Becke was a staunch Protestant, and he added some more of Tyndale’s glosses, along with a letter to Edward VI.

Matthew Bible, 1551:

In 1551, another edition of the Matthew bible was printed (Canterbury’s copy is this one). This was also produced by Edmund Becke, and this 1551 edition was simultaneously printed by John Day and Nicholas Hyll. This edition was advertised as a reprint of the 1549 Raynold and Hill edition of the Matthew Bible (which itself was a reprint of 1537). It was, however, largely based on the 1539 version of Richard Taverner. While the 1551 Matthew bible duplicated the prefatory material and editorial apparatus of the previous Taverner version, Becke added prologues and annotations to the biblical text for ‘better understanding of many hard places throughout the whole Bible’. It was the last printing of the Matthew Bible in early modern England.

This means that the marginal notes, prologues and summaries (or paratexts) in the 1551 Matthew bible come from a number of earlier bibles, all produced by Reformers. When preparing the 1537 Matthew Bible, for example, John Rogers copied the paratexts from an earlier bible published in France, the Lefèvre Bible of 1534 as well as from Coverdale’s English bible of 1535 and notes from Tyndale’s translations. As well as translating some of the summaries of the biblical chapters, Rogers copied other innovations from the Lefèvre bible including ‘a table of principle matters in the bible’.

Production & Printing:

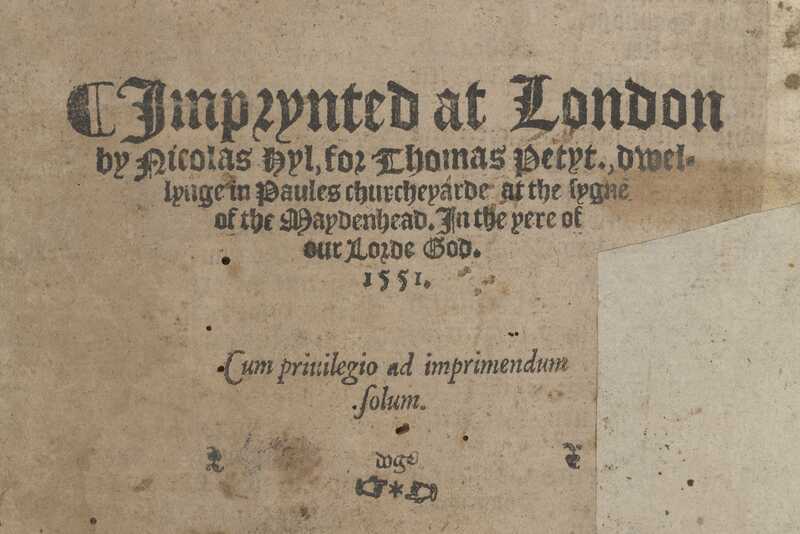

The printing of this bible was shared out between different publishers in London, including William Bonham, John Whyte, Robert Toye, Thomas Petyt and Richard Kele. Thus the colophon in some copies of the 1551 Matthew Bible reads: ‘Imprinted at London by Nicholas Hyll for certain honest men of the occupation whose names be upon their books’.

The Canterbury Copy has the name ‘T.Petyt’ on the title page (a similar copy can be seen in the British Library, London, U.K). Petyt was coming to the end of his career in 1551, he died a few years later. His shop was at St Paul’s Churchyard in London, the heart of the bookselling trade in England. From 1536 to 1561 he published and sold books from his property there, under the sign of the Maiden’s Head. In 1547, Thomas Raynald took over the operation of Petyt’s press, and by 1548, some of this printing material passed to William Hill (see above for both), showing the complex network of connections that made up the early modern English print trade. By 1551 Petyt had already collaborated with some of the other publishers of the Matthew Bible. In 1550, he published an edition of Chaucer’s works with William Bonham, Richard Kele and Robert Toy. Petyt started his publishing career as Reformed ideas were starting to take hold, and printed Tyndale Bibles for the Kings printer, Thomas Berthelet, in 1539 as well as later bibles (including this one) for Edward I. He continued to work under Mary I (1551-1558), and then printed Catholic works.

You can see elements of the complex printed and editing history in the layout of the bible. The biblical text is printed in double columns, which means more space for annotations and marginal notes. Successive editors (including Becke) have added additional material to help the reader. These include a list of contents before the chapters and notes at the end of many chapters. Further references are in the margins, with additional notes. There are fewer translation explanations in the 1551 bible, and the marginal notes and end notes instead focus on explaining points of theology and providing cross-references across the bible.

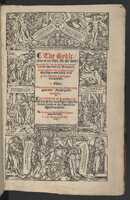

Some printing elements of earlier bibles have also been reused. The title page is the same as the title page used in Coverdale’s English translation of 1535, however in the Matthew Bible of 1551 the pictures are reversed. The text in the centre of the title page is also different. The border for the general title, and for the title of the New Testament books are similar to those used in Raynold and Hall’s edition of the Matthew Bible, published in 1549. In addition, the borders used for the titles of parts 2,3 and 4 consist of four corner blocks, echoing the layout of Henry VIII’s ‘official bible in English’, the Great Bible of 1549 and 1550.

Other Material:

The title pages are similar across the different copies, and copy the earlier Coverdale bible of 1535. At the top, God is represented by a Hebrew tetragrammaton. Down the right and left hand sides, key biblical moments are illustrated (eg Adam and Eve, Moses receiving the 10 commandments, Jesus appearing risen to his disciples after his crucifixion). At the bottom of the frontispiece, the king is portrayed passing the bible to the bishops, while noblemen kneel on the other side. Below are the royal coat of arms. This is not intended to be a realistic image of Edward VI (still a child in 1551), but rather represents the royal endorsement of this translation, initially under Henry VIII. By reusing or by copying an earlier frontispiece the publishers demonstrated the long pedigree of this edition, as well as official approval for this translation.

Before the biblical text, printers have included additional material that locates this English bible firmly in the Reformation of Edward VI and the new, Protestant, Church of England.

In 1549 and in 1552, Thomas Cranmer, archbishop of York, introduced two new prayerbooks in English as part of his programme to turn the Church of England into a truly Reformed Protestant Church. He was inspired by the progress of the Lutheran and Calvinist Reformations on the continent, and wanted the English Church to have an equally Protestant Church. The bible in English was an essential part of this process, but Cranmer needed to overturn centuries of Catholic traditions in the church including the traditional annual pattern of worship.

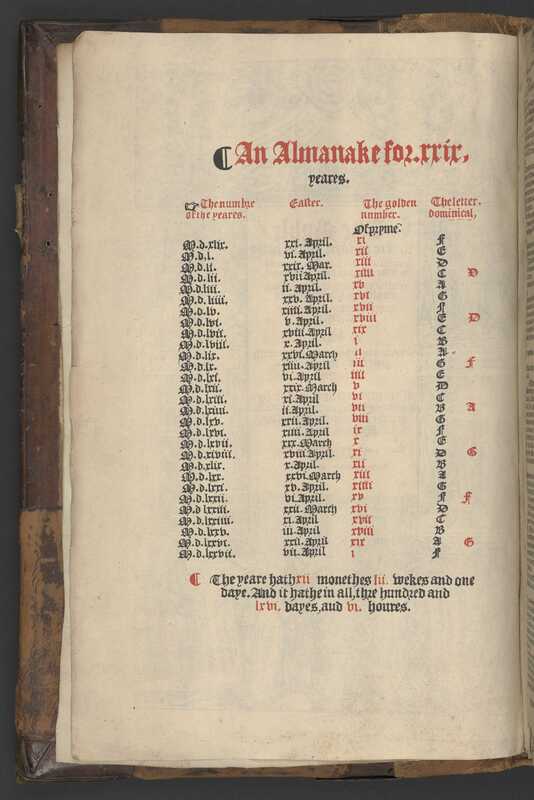

So attached to this bible are elements of this programme. On the reverse of the title page, there is an Almanac for 29 years from 1551 showing when Easter will be. Like the the title page, this is printed in black and red – a tricky combination of printing. Red and black were also the traditional colours for liturgical books, with red ink being used for instructions (the rubrics) to highlight important dates. Traditionally, Catholic calendars used red ink to mark Saint’s Days (the origins of the term ‘red letter days’). While Protestants rejected much of the Catholic church’s saint worship, the use of red and black ink for liturgical calendars persisted in the Church of England throughout the 16th century.

Private and Personal Use:

This copy of the bible is a folio, meaning it is a large bible designed to be used in public settings but the new translations of the bible were to read at home and used in private devotion as well as in the new church services. We can see both functions in the additional material (sometimes called paratexts) after the title page and before the biblical text.

The order of this material in the Canterbury copy differs from other copies of this 1551 edition that survive, since it is missing several sheets that usually come before the the table of principal matters, but this may have been when the copy was rebound and repaired.

Missing material:

In many other copies, there was an explanation of how the Bible is to be used in church services. The psalms were to be sung or said throughout the year, and then extracts from the Old Testament and New Testament were to be read in services in Matins (morning prayer) and Evensong. Different texts were set to be read throughout the year, but some parts of the Bible were to be left out: a note reads that ‘there be only certain lessons’ out of the ‘Apocalypse’ appointed.

The Bible was also to be read alone at home. After the almanac came a series of biblical quotations showing why it was so important to study the bible. This also explained the importance of the marginal notes and summaries which were included in this edition, as in earlier editions. The editor noted that he had included prologues and summaries along with ‘many plain annotations and expositions of such places as unto the simple unlearned seem hard to understand’.

Surviving material:

Other material is designed to help individuals to study the bible outside of church services, and some of this was originally inserted by John Rogers in 1537 (see above). As well as a guide to the kings of the Old Testament – which is missing from the Canterbury copy -there was a table of ‘principal matters’ in the bible. The Canterbury copy is missing the first pages of this (covering topics starting with a-c). Designed to help readers find key verses in the bible both for their own spiritual growth and to ‘confound the adversaries of the word of God’, it is possible to see concerns of Edwardian Protestants in the topics chosen (eg on ceremonies, or significantly on ‘election’ a key part of the emerging strain of Calvinist thought in 1551). The Canterbury copy also has a prologue, which further discussed the role of scripture in church worship and in personal spirituality, as well as suggesting how Evangelical ideas from the bible should be applied to English society.

Provenance of the Canterbury Matthew Bible (1551):

This Matthew bible was acquired by auction in 2022 from the Carl R Straubel collection. Straubel attended Canterbury College and was the author of several works on Canterbury History (though in 1954 P. A. Lawlor wrote that Straubel was ‘so busy deciding on the publication or rejection of other people’s books, his own literary work has been neglected’). Straubel was a well-known book-collector, based in Riccarton Christchurch. While he specialised in New Zealand and Pacific history, he also collected a few examples of ‘fine early European Printing’. Straubel’s son, Paul, owned two incunabula which had previously belonged to his father. Straubel managed to obtain a vast collection from Thomas Leonard Seddon, including this bible, who had a vast collection of over 3000 books and incunabula. Inside the front cover is Seddon’s bookplate, which was designed by Charles Sayer.

Seddon bought the Matthew Bible from a well-known rare book seller, Bernard Halliday, based in Leicester in the UK in December 1946. He paid £14 for it. In the aftermath of the second world war, communication and postage must have been tricky – the copy was delivered to Seddon at the Mayor’s Office in Fielding, North Island NZ.

Also found in the copy was a palm cross. These crosses were (and still are) handed out in Church of England services on Palm Sunday (the Sunday before Easter). Christians bend strips of palm into crosses in remembrance of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem, when he was greeted with waving palms. These crosses are then often used throughout the year as bookmarks in religious books, suggesting that this bible was being used into the 20th century.

The binding has some original features and looks remarkably like the bible on the frontispiece with the metal work in the centre, on each corner of the bible. Along with the size, this shows that it this copy of the Matthew Bible was to be used publicly, probably at the front of the church during services. There are also the remains of clasps to keep the book closed and protect the paper. Repairs have been made over the last 500 years where the leather has worn away or been damaged and replacing the spine.

References:

Vivienne Westbrook, ‘Richard Taverner Revising Tyndale’, Reformation (1997), 2, pp. 191-205.

John N. King, ‘Edmund Becke, fl. 1549-1551), Oxford Dictionary National Biography (2004).

Alexandra Gillespie, ‘Thomas Petyt [Petit]’, b. 1494-1565/6), Oxford Dictionary National Biography (2004), (rev.2008).

Ezra Horbury, ‘The Bible Abbreviated: Summaries in Early Modern English Bibles’, Harvard Theology Review 112: 2 (2019)

Debora Suger, Paratexts of the English Bible, 1525-1611 (2022).

CHR Taylor (ed.) A Roll of Book Collectors in New Zealand (Wellington: The New Zealand Ex libris and Book lovers Society, 1958)

P. A. Lawlor, Books and Bookmen: new Zealand and Overseas (Wellington: Whitcombe and Tombs Limited, 1954).

Citing information:

Rosamund Oates. Matthew Bible 1551. Canterbury Renaissance and Reformation, https://digitalvoyages.canterbury.ac.nz/omeka-s/s/ren_ref/page/matthew_bible (Access date)