A leaf from the Tyndale, Matthew Bible of 1549 (Report)

This is a reprint of a bible first published in 1539, and known as the ‘Matthew version’. It is based on the English translations of the bible by William Tyndale (c.1494-1536) and Myles Coverdale (1488-1569). When it was first published in 1539, ‘Thomas Matthew’ was recorded as the translator. Although some historians suggested that ‘Thomas Matthew’ was a pseudonym of John Rogers – a close friend of Tyndale, AS Herbert argues that it referred to William Tyndale himself, and David Daniels thought it was chosen since Thomas and Matthew were two of Jesus’ apostles. This is often referred to as the ‘bug bible’ (as are later versions of the Matthew bible) because of the translation of Psalm 91:4, ‘thou shalt not be afraid for any bugs by night’. This translation can also be seen in Coverdale’s 1535 edition of the bible. In the 1539 Great Bible, Coverdale replaced the word ‘bugs’ with ‘terror’.

William Tyndale:

William Tyndale was an early adopter of Reformed thought, later called Protestantism. Protestantism put the bible, rather than church ceremonies, at the heart of their worship. Reformers believed that everyone should be able to access the bile int heir own language, an idea many Catholics thought was heresy. Tyndale translated the New Testament into English using Martin Luther’s German New Testament, which he completed in the Lutheran city of Worms in 1526. This was the very first bible printed in English and was banned in England immediately. Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall oversaw a burning of Tyndale’s New Testament in London in October 1526.

As David Daniell notes, Tyndale’s 1526 New Testament is a ‘treasure of English-speaking culture’, introducing phrases including ‘the spirit is willing’, ‘fight the good fight’, and ‘the powers that be’. Tyndale continued to work on his translation after this first edition and in 1534 published a revised edition of the New Testament. This 1534 edition was to influence all subsequent English bibles (around 83% of the King James’ New Testament is taken from Tyndale’s 1534 edition).

William Tyndale also learned Hebrew (perhaps while he was in Worms, where there were rabbinic scholars). He then translated part of the Old Testament (the five books of the Pentateuch) into English, publishing them in 1530. By 1535, he had translated - but not published - the historical books of the Old Testament (this did not include the Book of Job, which this leaf is from).

William Tyndale also attacked Henry VIII and his support for the Catholic Church. Thomas More, a committed Catholic and Henry VIII’s Lord Chancellor, wrote several attacks on Tyndale, denouncing him as a heretic. Tyndale felt safe on the continent, but in 1535 he was arrested and imprisoned by the Inquisition. He was condemned as a heretic and burned in 1536 (though he was strangled before being burned).

Myles Coverdale:

English cleric Myles Coverdale started to become interested in Reformed ideas towards the end of the 1520s, eventually attracting attention for his beliefs. Afraid of being executed as a heretic, he fled overseas to continental Europe. There Coverdale started to work on his own English translation of the New Testament. The Elizabethan historian, John Foxe, recorded that in 1529 Coverdale was in Hamburg helping Tyndale to translate the Pentateuch – however, Coverdale did not know any Hebrew then, and so it seems likely that Coverdale’s Old Testament translations were done later, on his own. Coverdale did eventually join up with John Rogers and William Tyndale in Antwerp. In 1535 Coverdale was the first to publish the whole bible in English (Old and New Testaments). Unlike Tyndale, he did not work from Greek and Hebrew, but relied on other people’s translations including Luther’s German translation, the Vulgate (translated into Latin) and Tyndale’s translations into English. Coverdale returned to England in 1535.

1537 Matthew’s Bible:

Henry VIII vacillated between supporting Reformed ideas and attacking the Papacy, and sometimes embracing Catholic doctrine. By 1537, not only had Henry VIII established himself as the head of the Church in England – breaking away from the Catholic Church – but he was surrounded by advisors like Thomas Cromwell and Thomas Cranmer who promoted Reformed, Lutheran ideas. These included making the bible available in English.

So, in 1537 a new English bible was printed in Antwerp (although it was printed for two publishers, Grafton and Whitchurch, who were based in London). Much of it was based on William Tyndale’s translations. Tyndale’s friend, John Rogers – himself a talented scholar – collected Tyndale’s notes and produced an Old Testament based on Tyndale’s Pentateuch along with Tyndale’s translations of the historical books of the Old Testament. Since Tyndale had not finished translating the Old Testament, John Rogers used translations by Myles Coverdale for the rest of the Old Testament along with Coverdale’s translation of the Apocrypha. However, Rogers did re-translate some of Coverdale’s text, including the first chapters of Job.

Since Tyndale had been declared a heretic, his name could not be used on the bible and Rogers claimed that it was a translation by ‘Thomas Matthew’. The bible was licensed by the King, and soon all copies sold out. In 1537, Thomas Cranmer wrote to Thomas Cromwell thanking him for securing the king’s permission for the Matthew bible, saying it gave him more pleasure than if he had been given a thousand pounds (a fortune at the time). ‘Matthew’s Bible’ followed Tyndale and Coverdale in ordering the books of the bible in the same way that Luther had, furthering the Reformed tone of this edition.

Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell employed Myles Coverdale to revise the Matthew’s bible further, and in 1539 ‘Great Bible’ was published in England by Grafton and Whitchurch). Endorsed by Henry VIII, this became the official Bible of the Church of England. Another theologian, Richard Taverner was also revising the Matthew bible, and he produced a version of the Matthew Bible in 1539 – shortly before the ‘Great Bible’.

1549 Matthew Bible:

This is a leaf from a 1549 edition of the Matthew Bible. In 1547, Henry VIII was succeeded by his son, Edward VI, a committed Protestant, who ushered in a new Protestant church and there was a surge in demand for English bibles.

In August 1549, in London, the printer John Day, produced a version of the 1537 Matthew’s bible with his partner William Seres, which was edited by Edmund Becke. This revised edition was more Protestant in its tone and included notes on the Book of Revelations taken from the Image of Two Churches by the radical John Bale. Earlier in 1548, Day and Serres had published a stand-alone edition of William Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament, and included the arms of Catherine Parr – Queen of England and last of Henry VIII’s wives - suggesting that she supported Tyndale’s ideas.

Soon afterwards, two other London printers, Thomas Raynald and William Hill, also in London, printed a copy of the Matthew bible. Unlike Day’s 1549 version of the Matthew Bible, Raynald and Hill largely reproduced the 1537 Matthew bible.

Text, typology and layout:

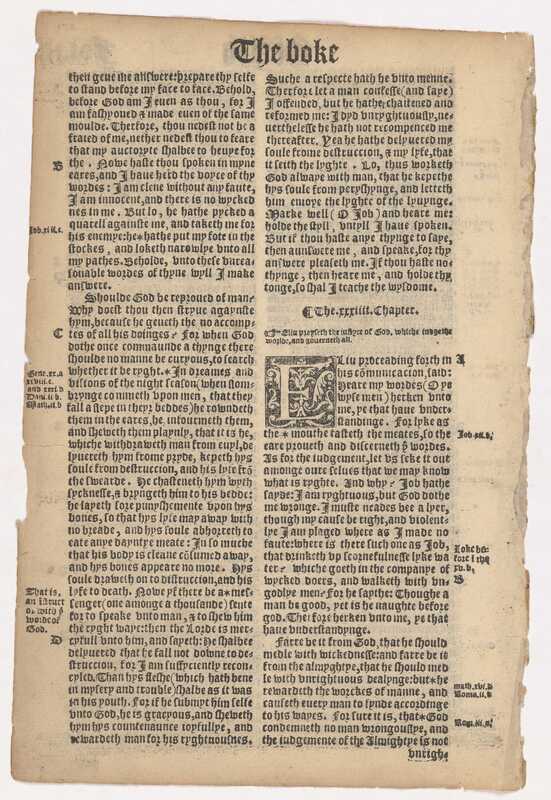

As Reformers began to produce vernacular translations of the bible, they started to include marginal notes. These could have many different purposes: to explain how the author had translated a passage; to explain a point of theology: or to provide a cross-reference to another part of the bible. The marginal notes could often contain ‘glosses’ which interpreted the bible according to different theological standpoints. (Most famously in England was the Genevan Bible, whose interpretive notes were criticised by James I).

One of the main criticisms by the Catholic Church of Tyndale’s biblical translations were his ‘pestilent glosses’, which reflected his Reformed beliefs. These could be seen in both his expositions and his choice of words (for example he chose words like ‘congregation; instead of Church, and ‘senior’ or ‘elder’ instead of ‘priest’. This supported a Reformed (later Protestant) view of the priesthood of all believers – that all men and women could connect directly with God and were not reliant on the priestly hierarchy of the Catholic Church).

When John Rogers produced the 1537 Matthew bible, he kept some of Tyndale’s notes and also added his own. It was Rogers who added the marginal cross-references, while many of the longer notes (see below) came from Tyndale’s 1534 edition. John Rogers also introduced summaries and glosses on each chapter. He had encountered this in a bible published by Lefèvre in 1534, and he copied some of those summaries along with summaries he found in Coverdale’s 1535 bible into the Matthew bible.

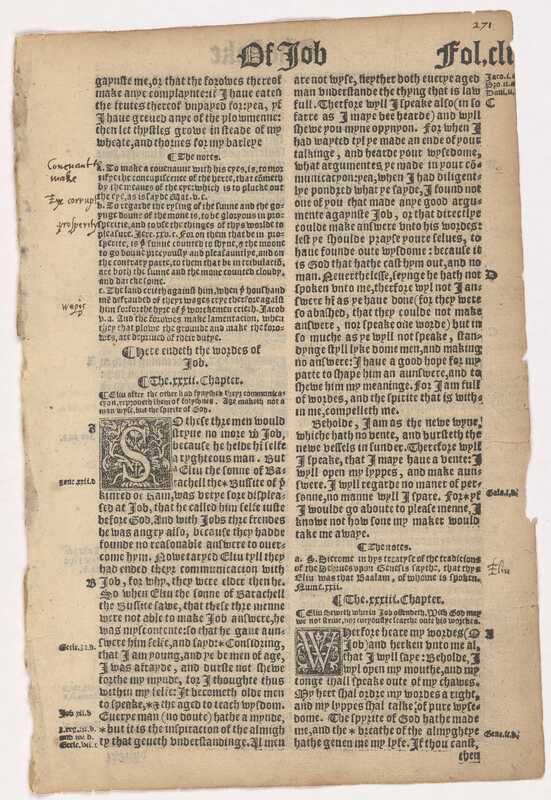

This sheet shows both marginal notes which provide cross references, explanatory notes and longer notes at the end of the chapter. These last notes are the interpretative framework, and so a later reader has made annotations in ink next to the gloss including highlighting the use of the work ‘covenant’ – an important part of Protestant, and later Puritan or Calvinist thought.

References:

Lucy Wooding, ‘Encountering the Word of God’, English Historical Review 136 (2021) Debora Suger, Paratexts of the English Bible, 1525-1611 (2022).

Citing information:

Rosamund Oates. A leaf from the Tyndale, Matthew Bible of 1549. Canterbury Renaissance and Reformation , https://digitalvoyages.canterbury.ac.nz/omeka-s/s/ren_ref/page/matthew_bible_leaf (Access date)