The Nuremberg Chronicle (Report)

Hartmann Schedel. Liber Chronicarum (Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1493)

The Liber Chronicarum, more popularly known as the ‘Nuremberg Chronicle’ was printed in Nuremberg in 1493 by Anton Koberger, (c. 1440-1513) and compiled by Hartman Schedel (1440-1515). The first edition was in Latin in 1493, and a German translation (by George Alt) was published later that year. The Liber Chronicarum was so popular that successive printers produced cheaper, inferior copies. The Canterbury copy is a German 1st edition from 1493. Produced in the first decades of printing, it is called an incunable.

Context

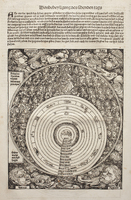

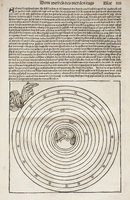

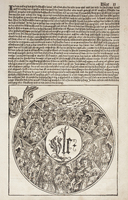

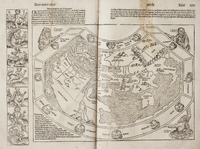

The Liber Chronicarum is a universal history, combining eschatological, biblical, and secular histories to provide a history of the world from the start of time to the end of the world. It shows the impact of the Renaissance as well as the continuing impact of Christianity on thinking about history. Schedel used the traditional chronology of the bible to divide the history of mankind into seven stages in the Chronicle. The first age included Creation, the Garden of Eden and Noah’s Ark. Stages 2,3, 4 and 5 were based on stories in the Old Testament and the sixth stage started with the birth of Christ and continued up to 1493 when the book was produced. The seventh stage had yet to come – it was the arrival of the Antichrist and the Last Judgement. Many copies included blank pages before the pictures of the Last Judgement for readers write for themselves an account of what had happened between the 1493 and the end of the world. The Liber Chronicarum shows the influence of new Renaissance ideas. Schedel used Italian Humanist texts to write this history including Flavio Biondo’s Decades and Giacomo Filippo Foresti da Bergamo’s Supplementum Chronicarum. These books were in Schedel’s library, along with texts on law, medicine, Greek and Latin history and geography.

What is special about this copy?

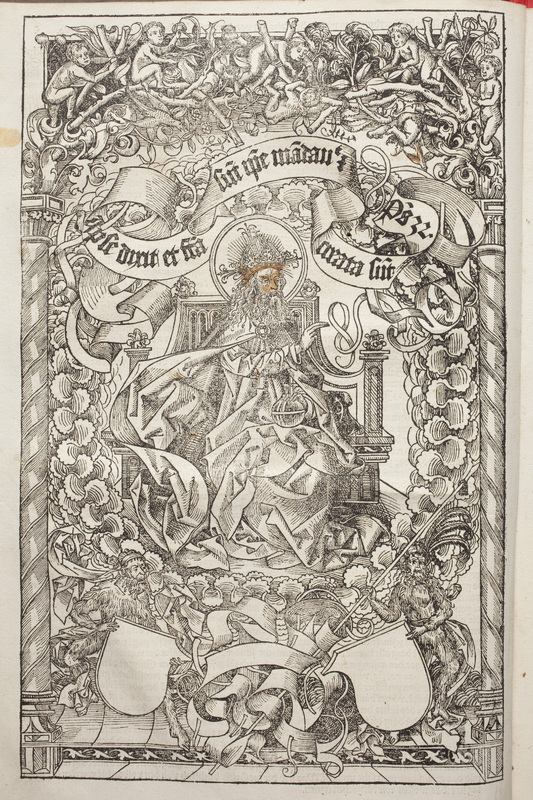

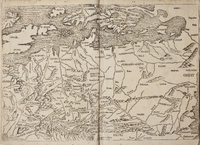

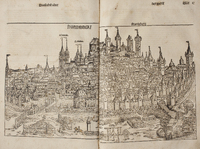

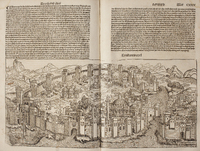

The Liber Chronicarum is richly decorated with woodcuts, portraying the places and people discussed in the history. Drafts of the Chronicle in Schedel’s hand show that illustrations were always an integral part of the work, and two prominent Nuremberg artists were employed to supply the images. These were Wilhelm Pleyndenworff (c. 1450-1494) and Michael Wolgemut (c.1434 -1519). It is possible that Albrecht Dürer, who became famous as a woodcut artist, was involved in the images because he was training with Wolgemut in the 1480s. The Latin and German 1493 editions have around 1800 illustrations from around 645 woodblocks, and you will see that some of them are used repeatedly throughout. There are also lavish pictures of cities (mainly in modern Germany) and maps, showing the world-view of a 15th century European. This copy was one of the two original print runs by Schedel and Koberger, and was a huge financial undertaking. It was funded by two rich men in Nuremberg, one of whom was the city physician and was a significant moment in the history of printing. The production of such a lavish book required significant investment in paper, machinery and expertise in printing. The backers also relied on a network of trade routes across Europe to sell copies of this lavish book. The Liber Chronicarum was read by generations of people, and some of the later readers of this copy seem to have been Protestant readers who disagreed with some of the Catholic views of history.

This copy was one of the two original print runs by Schedel and Koberger and was a huge financial undertaking. It was funded by two rich men in Nuremberg, one of whom was the city physician and was a significant moment in the history of printing. The production of such a lavish book required significant investment in paper, machinery and expertise in printing. The backers also relied on a network of trade routes across Europe to sell copies of this lavish book. The Liber Chronicarum was read by generations of people, and some of the later readers of this copy seem to have been Protestant readers who disagreed with some of the Catholic views of history. In the Canterbury Nuremberg Chronicle we can see that someone has defaced images of popes on sigs 181(v),185 (v), 232v. These annotations reflect popular anti-Catholic stories about the papacy spread by Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Someone has added a picture of a devil to the shoulder of Pope Silvester, who was reported to have learnt sorcery when studying in the Islamic cities of Cordoba and Seville. Pope Benedict VIII has a man with an axe on his shoulder because he was engaged in a long-running struggle with another person who claimed to be Pope. Benedict IX also has a devil on his shoulder – perhaps because he was the only pope who was said to have ‘sold’ the position of pope. Successive readers have written comments and sometimes doodled in the margins of this copy, but many of these have been cut off when the book was later ‘tidied up’ for sale.

Canterbury Connections

Before this copy of the Nuremberg Chronicle made its way to Canterbury, it had many different owners. This was a prestigious book to own, and so many owners have written their name on the front page. This includes owners from the 16th century onwards. Later owners include e PGA Culeman from Hanover (1836) and George Grazebrook, an businessman and antiquary who appears to have acquired the Chronicle in 1875 while he was working and living in Liverpool (U.K). The last owners of this work before it found its way to UC were the Hibbard family of New Zealand.

It was long believed that the UC Nuremberg Chronicle came to the university with Peter Lobard's Sentences, which was gifted by the Coberger family. This proved to not be the case and was confirmed when the Coberger family were consulted in 2017. It is likely that the Chronicle came to UC from a family member of Benjamin Hibbard along with a few other items from his vast collection.

Further Reading:

Rosamund Oates, Commentary Article: Liber Chronicarum in Bloomsbury Medieval Studies (Bloomsbury Medieval Studies Platform - subscription required)

Rosamund Oates and Nina Adamova, Reading the Nuremberg Chronicle https://nurembergchronicle.co.uk

Christopher Reske, Die Produktion Der Schedelschen Weltchronik in Nürnberg: The Production of Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle (2000)

A. Wilson, The Making of the Nuremberg Chronicle (1976)

Citing information:

Rosamund Oates and Damian Cairns. Liber Chronicarum. Canterbury Renaissance and Reformation, https://digitalvoyages.canterbury.ac.nz/omeka-s/s/ren_ref/page/liber_chronicarum (Access date)