Peter Lombard Sententiarum Libri IV [commentary Bonaventura, ed. Johan Beckenhub] (Report)

Peter Lombard. [pt.1, fol.1 verso:] Joh'es Bekenhaub Moguntin' euagelice theologie summo doctori dno Nicolao tinctoris de guntzenhausen im pialis eccl'ie bambergensis pdicatori salute. [fol.3 recto:] Celebratissimi patris domini bonaueture...prologus ir primu libru sententia'. [Nurnberge : Anthonius Koberger, 1491]

Peter Lombard Sententiarum Libri IV (commentary Bonaventura, ed. Johan Beckenhub) (Anton Koberger: Nuremberg, 1491) Also catalogued as: Celebratissimi patris domini Bonauenture ordinis Mino[rum] ... p[er]lustratio in archana tercij libri S[e]n[tent]ia[rum] Joh'es Bekenhaub Moguntin' euagelice theologie summo doctori dno Nicolao tinctoris de guntzenhausen im pialis eccl'ie bambergensis pdicatori salute. [fol.3 recto:] Celebratissimi patris domini bonaueture...prologus ir primu libru sententia'.

Peter Lombard (c.1096-1160) was Bishop of Paris and a leading theologian of the medieval Church. The Four Books of Sentences (or the Sententiae) was an important work of scholasticism. It effectively became a theology textbook at European universities throughout the medieval period up to the 16th century. The Sentences were an attempt to provide a systematic investigation of theological ideas by collecting all patristic interpretations (or 'sententiae') of Scripture together. The importance of the Sentences is indicated by the high number of surviving manuscripts from the medieval period (between 600 and 900). All leading thinkers wrote commentaries on Lombard’s Sentences, including William of Ockham, Thomas Aquinas, and St Bonaventura (c.1221-1274), a Franciscan theologian. This book is a printing of Bonaventura’s commentaries on Peter Lombard’s Sentences, which was considered one of Bonaventura’s major theological works

Why is it significant?

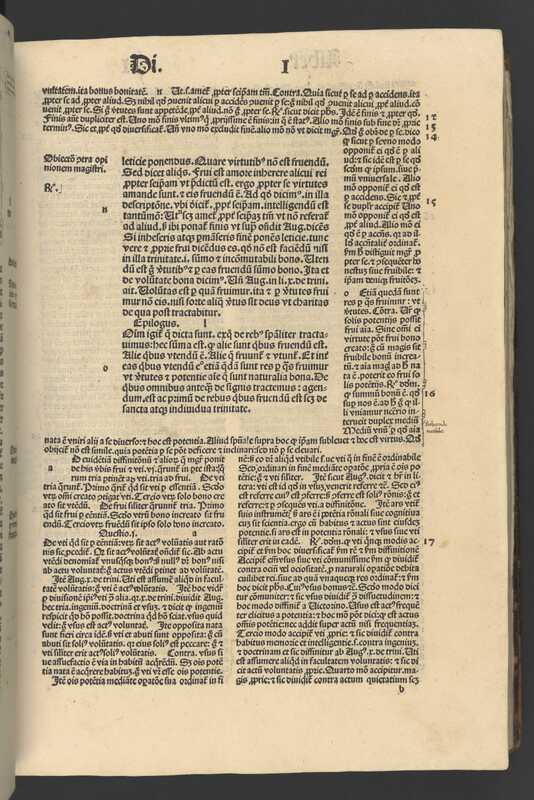

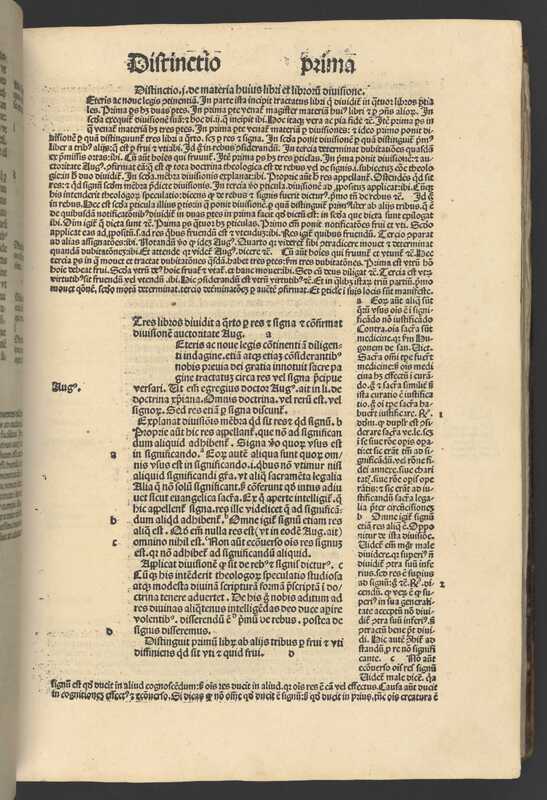

This edition was published by Anton Koberger in Nuremberg sometime after 2 March 1491. Koberger owned one of the largest printing and publishing houses in Gemany, with around 24 presses, and employed a number of skilled artisans including printers, typesetters, typefounders and illuminators too. As well as printing, Koberger established networks to distribute his books and both were essential to his success. Koberger also developed sophisticated techniques in printing, some of which can be seen in this copy. Peter Lombard’s text is separated from Bonaventura’s commentary by different typography (see for example, Book 1 sig A7r and Book 1 sig.A8r. ) Lombard’s original text is printed with side notes in the inner margin and a gloss on the outer margin, with Bonaventura’s commentary following on. There are spaces throughout to make further notes, and this would have been a useful text for those studying theology. It was a complicated layout, combining different blocks of text and different font sizes and shows the development of Koberg’s printing techniques.

Multiple editions of Peter Lombard’s Sentences (with commentaries by different authors) were published in the first years of printing because it was such a popular text. Bonaventura’s commentaries were also popular and so this combination was likely to have been a profitable publication. This edition was edited by Johann Beckenhub. He had studied at the University of Heidleburg in the mid 15th century where he became interested in printing – then a new invention. He became a proof reader and academic advisor in Strasbourg and Regensburg, later working with Koberger in Nuremberg. This was one of several texts he produced with Koberger. In 1491, Koberger published the Sententiae in four books which may have helped to spread the cost of production and allowed Koberger to start selling the earlier books before the later ones were completed. There are many surviving volumes from the 1491 printing, though most are not complete copies ( 1-4) . Canterbury’s copy includes books 1 and 2, which address the nature of God, the doctrine of the Trinity and the creation of the world, but lacks 3 and 4. Like many incunables, there is no title page. The printer, Anton Koberger, is named in a letter which includes a poem, at the start of volume I from Johann Beckenaub (sig. a3r).

There is also a letter from Nicolaus Tinctor to Beckenhaub which is dated which is 1491 mensis Marcii die s[e]c[un]do. Tinctor was a Franciscan theologian, based in Germany, was known for his work on Dons Scotus – another commentator on the Sententiae – and Tinctor’s letter was a seal of approval on Beckenhaub’s work. In some surviving 1491 copies, this letter is at the end of book four but in the Canterbury copy (and other copies) it is at the start of book 1. the The colophon, which includes the date and place of publication is at the end of voume four, (and not included in the Canterbury copy).

What is unique about this copy?

Canterbury’s copy is unusual, and may have been put together in the Koberger workshops in the decades after 1491. Like many of Koberger’s 1491 edition of the Sententiae, the Canterbury copy has an index at the end of each book. This is headed ‘Ordo questionium divi Bonaventure’ (a table of St Bonaventure’s questions), and is a guide to the topics covered in Bonventure’s commentary on each book of the Sententiae.

But the Canterbury copy has an unusual addition – a much more detailed index at the front of the volume which is missing from other 1491 editions of Bonaventure’s commentary on Lombard’s Sententiae. This index appears to have been printed at a later date, possibly up to twenty years after the main body of the text, and so this book has been put together in the decades after the initial printing.

This detailed index was another production by Anton Koberger and Johannes Beckenhaus, sometime between 1491 and 1494. They may have wanted to build on the success of their Sententiae of 1491 or alternatively to differentiate their edition of Bonaventure’s commentaries on the Sententiae from others that were being produced in Germany at the same time.

Whatever the cause, sometime before 1494, they produced a further addition to the Sententiae. They called this the Tabula super libros sententiarum Petri Lombardi cum Bonaventura. The work consisted of two parts: firstly, a detailed index running to around 180 pages (or around 90 folios), which was followed by a more discursive summary of Bonaventure’s work.[1] Beckenhaub wrote a brief introduction to the Tabula (sig. a2r.) in the Canterbury copy, explaingin that it was to help readers to identity key passages in his edition of the Sententiae. When Koberger produced new editions of Bonaventura’s commentary on the Sententiae in the years following 1494, he incorporated the new Tabula. After 1494, the Tabula was published as book 5 in the series, following on from the original books 1-4.

The Canterbury copy of the Sententiae (printed in 1491) has a version of the first part of the Tabula (printed 1494-1520) stuck in at the front of volumes 1 and 2. This suggests that this copy was put together in Koberger’s workshops where both books may have been available. This happened with another copy, now in the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, where the Tabula from 1494 was bound with book 4 of the 1491 edition of the Sententiae.[2] However, the Tabula used in the Canterbury copy of the Sentenitae is not the first edition produced around 1494. It has a slightly different layout to the first edition, and some differences in content– so when was it printed?[3] . The answer demonstrates how complex an operation the Koberger publishing house was, and the extent to which books could be collated over a long period of time.

Versions of the Tabula were produced in the following decades by different members of the Koberger family and in different places. In 1500, Anton Koberger published a new edition of the Sententiae with the Tabula as volume 5 (ISTC ip00488000).[4] Later, Anton Koberger gradually moved out of printing books himself, become more akin to a modern publisher, arranging the printing and organising the distribution of books. In 1510 and 1515 the Koberger house published new editions of the Sententiae. This time, Koberger’s sons, Anton and Johannes Koberger, employed Jacques Sacon - a printer in the French city of Lyons - to print the new editions of the the Sententiae (ISTC ip00489000 and ip004892000). This new print run included the Tabula which was included as volume five, though sometimes it was available on it its own. From 1510, the Tabula was renamed: Index alphabeticus siue repertorium Iohannis beckenhaub in scripta diui bonauenture super quattuor libris sententiarum.[5]

The Canterbury copy of the Sententiae appears unique among surviving copies of this popular text. That is because it combines text from 1491 with a later index. The Canterbury Index may be from the edition printed in Lyons in 1510. It differs in layout from surviving copies of the Tabula printed in Nuremberg c. 1494 and the Index printed in Lyons 1515. Both the layout, and the printers’ marks are different as the work progresses. So the Canterbury copy was either printed by a different printer – or was part of a different print run to the c.1494 and 1515 copies. It is also missing the first leaf, which is a title page.

This offers an insight into how printers and booksellers operated, putting together volumes over decades. It seems likely that the Koberger printing houses or publishing company were responsible for the compilation of the Canterbury copy, since all elements were produced by the Koberger press. If this had been put together by a later bookseller, or collector, it is possible that they would have combined texts from different printers. Koberger did not have a monopoly over the Sententiae, he was unable even to claim sole right to publish Beckenhaub’s edition. There were many different versions of Bonaventure’s commentary on the Sententiae produced by other publishers, including versions of this text edited by Beckenhaub. In 1493, for example, rival printers to the Kobergers in Freiburg im Breisgau, Wolfgan Lachner and Kilian Fischer, produced their own version of Beckenhaub’s edition of Bonaventure’s commentary on the Sententiae.( ISTC ip00487000).

Another element of the Canterbury copy that makes it unique is the extent to which it is ‘unfinished’. When Koberger printed the text, he left blank spaces for later artists or artisans to do the ‘rubrication’. This meant adding decorative capital letters and marks throughout the text (known as pilcrows) to show when a new idea or sentence began. In the first years of printing this was done by hand, blurring the distinction between manuscripts and print. Because this copy it is not finished, so we can see the process of rubrication. There is rubrication on 10 sides – two pages of the prologue (sig. a3v-a4r), and in book 1 sig. c2v-c6v (see attached). If you look at the earlier pages, however you can see the process of rubrication. There are blanks in the text where pilcrows or capital letters should have been painted in, but were not. Sometimes guidelines were printed to help the rubricator, sometimes tiny versions of the capital letter were included in the blank square to show what letter was missing. And in one instance, someone has drawn in a pilcrow, ready to be inked, but this has not happened.

If we compare the Canterbury copy with surviving copies elsewhere (for example this one in Munich), we can see there were standard rubrications that were used. Rubricators often switched between blue and red. Koberger had inhouse rubricators, but many booksellers employed their own rubricators to, allowing a level of personalisation among otherwise standardised printed copies. This copy has fairly basic rubrication, and limited decoration of capitals. Perhaps only a few sheets were done in this volume to demonstrate the level of decoration available at different prices (this being an example of a more basic rubrication). Or perhaps, these sheets were mistakenly added from another copy, which was rubricated in its entirety.

You can also see evidence of how book binders used scrap paper (in this instance with Hebrew text on it) to bind books, either as paste downs at the front, or to strengthen the spine.

The Canterbury Connection: Readers and Collectors.

Another interesting feature of the Canterbury copy of the Sentences are the readers’ marks (or annotations) throughout. Renaissance readers expected to read with a pen in their hand, and annotating was an important part of absorbing the information and making notes to guide future reading. The detailed index (or Tabulae) at the front of the Cantebrury copy of the Sententiae helped students to access the different themes addressed in the Sententiae and in Bonaventure’s commentary. We can see that one reader has annotated the index with different marks. One common mark was the trefoil, which a reader of this volume has used to highlight topics of interest. In some places (eg Tabula/Index sig m4r), the reader has changed the trefoil into a manicule, a picture of a pointed finger with an extravagant cuff. Early modern readers often used manicules to highlight particularly important passages, and each reader developed manicules that were unique to them and acted as a sort of reading signature. You can see a different type of manicule, for example, in Bk i. sig. k3r. Sometimes readers also wrote notes to help them navigate the text. For example on sig. l4v. someone appears to have written ‘original sin’ (in Latin) in the margin next to the index reference for this topic while further on, the same person has summarised the main features of an argument in the margins, and highlighted the relevant text (Bk I, sig. a7v.) Different annotations are in different coloured ink, showing multiple readings and annotations at different times. (eg. Bk 1, sig b3r), there are different hands too meaning that several different people read and annotated this.

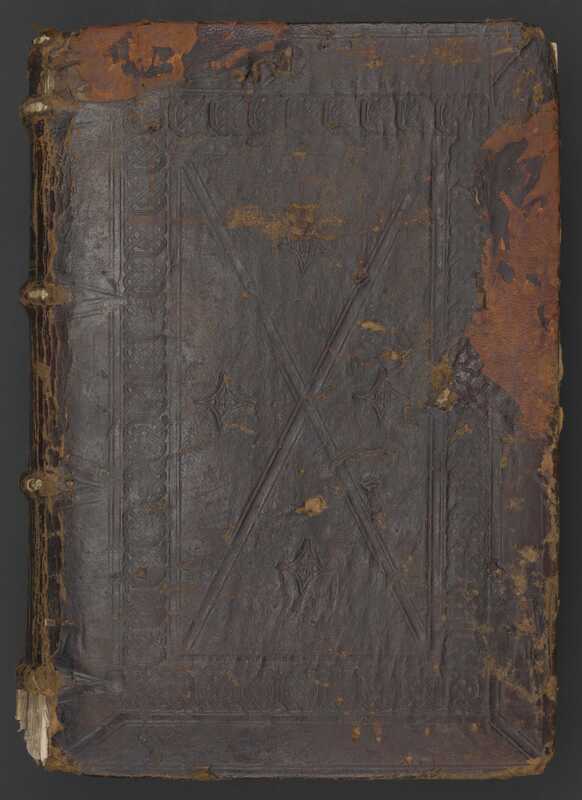

This copy originally belonged in a library, and was there in the century after it was printed. It was stored ‘fore edge’ with the spine against the wall (it seems like the wrong way round to us), and so it has a number on the fore edge which helped people identify it. The book was later rebound, and so now it has a title on the spine where we expect to see it.

Provenance:

The UC copy was not in the first survey of the incunabula of Australia and New Zealand, undertaken in 1966. However, a different edition of Bonaventura’s commentary on Peter Lombard’s Sententiae is – this one published in Venice in 1477 is held in the Auckland Public Library (BMC V 254, Jain Coinger 3538).

The UC copy was recieved from the Coberger family, a well known Canterbury name in alpine pursuits and business, and ancestors of the printer of this work, Anton Koberger . The date of donation is unclear but it was confirmed that the item was indeed gifted to UC when the Coberger family visited the Macmillan Brown library to view the work in 2017.

Footnotes:

-

A copy of the Tabula in Bibliothek der Benediktinerabtei in Ottobeuren (Germany) has an buyer's inscription with the date 1494, however the print historian, Goff thought that the Tabula was printed around 1500. (Goff B292).

-

Johannes Beckenhaus, Tabula super libros sententiarum Petri Lombardi cum Bonaventura, (Nuremberg, Anton KOberger 1494-1500?). Groningen, Universiteitsbibliotheek (NL) Shelfmark: uklu INC 52 (2.2)

-

Johannes Beckenhaus, Tabula super libros sententiarum Petri Lombardi cum Bonaventura, (Nuremberg, Anton KOberger 1494-1500?). ISTC ib00292000. See for example the digitised copy at Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München (Germany) https://nbn-resolving.org/urn/resolver.pl?urn=urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb00043965-1

-

Peter Lombard, Sententiarum libri IV. Comm: S. Bonaventura. Add: Johannes Beckenhaub: Tabula. Articuli in Anglia et Parisiis condemnati (Nuremberg: Anton Koberger, 1500), vol. 5. Goff P‑488T his too is different from the Tabula or Index included in the Canterbury copy. See for example the copy in München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb00038568?page=,1

-

See http://frenchpostincunables.djshaw.co.uk/index.php?title=Bonaventure,_Saint,_Super_quatuor_libris_Sententiarum._1515._2°._Lyon:_Jacques_Sacon,_for_Anton_Koberger for the type faces used. You can also see a a digitised copy here https://i3f.vls.io/?collection=i3fblbk&id=https%3A%2F%2Fdigital.blb-karlsruhe.de%2Fi3f%2Fv20%2F7857218%2Fmanifest. USTC no. 144444.

Further reading:

Geldner, Ferdinand, "Beckenhub, Johann" in: Neue Deutsche Biographie 1 (1953), pp. 709-710 [online version]; URL: https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd100124232.html#ndbcontent

GOFF: Frederick R. Goff Incunabula in American libraries: a third census. Millwood (N.Y.), 1973. (Reproduced from the annotated copy of the original edition (New York, 1964) maintained by Goff). (Supplement. New York, 1972.) This edition is given the number GOFF P486

BMC: Catalogue of books printed in the XVth century now in the British Museum [British Library]. 13 parts. London, ’t Goy-Houten, 1963-2007. This edition in volume2, p. 433

Rosamund Oates. Peter Lombard Sententiarum Libri IV . Canterbury Renaissance and Reformation, https://digitalvoyages.canterbury.ac.nz/omeka-s/s/ren_ref/page/lombard_sententiarum (Access date)