Le terze rime (Report)

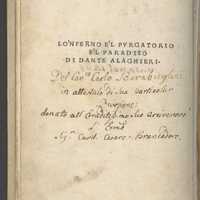

Le terze rime [lo'nferno e'l purgatorio e'l paradiso]. [Venetiis : In aedibus Aldi, 1502]

Report written by UC student, Jasmine Ryan, 2024. (Initially enrolled in an Independent Course of Study)

The University of Canterbury’s copy of Le Terze Rime, or The Divine Comedy, printed by Aldus Manutius in 1502 provides a scope of insight into the history of printing and the invention of movable type. Against the backdrop of the Italian Renaissance, Manutius, a humanist scholar and printer, produced portable editions of classics to a wide audience across Europe. As a flourishing commercial, artistic and intellectual capital, Renaissance Venice sets the scene for the success of Manutius’ printing press. Dante’s Le Terze Rime from the early fourteenth century was a masterpiece of medieval Christian literature written in Tuscan dialect, which was later standardised into the modern Italian language. The new gatekeepers of knowledge, the printer-publisher industry caused widespread dissemination of popular and humanist texts. Manutius is not only a good example of a successful printer-publisher of many classical texts, but is also credited with the creation of the popular, portable classic – the octavo, a descendant of the modern paperback. Le Terze Rime is featured in this format. Aldus’ invention of the portable classic helped define the printed Renaissance.

Humanism and its principles derived from critical analysis of 'forgotten' classical manuscripts like those by Cicero and Virgil. Arising in the fourteenth century, Petrarch and Boccaccio of Florence were key pioneers of the revival of classical manuscripts that had been copied out by Carolingian scribes during the ninth and tenth centuries. Humanists produced new editions of these texts, interested in restoring the classical style with accuracy. Humanism became a mainstream phenomenon, defining the new culture of the Renaissance. A key humanist concept, imitatio, emerged as intellectuals emulated Classical writers, while simultaneously believing in instinct and individual interpretation, bringing new ways of interpreting classical texts. Humanist printer-publishers were keen to make classics available to working class humanist scholars for their work reinterpreting classical thinkers. The famous 1502 Aldine edition of The Divine Comedy was published in its context as a great piece of medieval Christian literature, a valuable text for portability and accessibility alongside the revered classical writers. In admiration of Dante’s literature, the poet Petrarch saw them as a representation of the rebirth of poetry in the same way that ancient texts were given new life by humanists.

Aldus Manutius was an important figure of the Italian Renaissance, both as a humanist scholar and as a pioneer of development in the field of printing. The printing press of the fifteenth century was enabled by two recent developments. Paper was now made from rags as opposed to parchment or vellum, a thirteenth century development already known to China, and Gutenberg’s movable type printing of the mid-fifteenth century allowed letters to be rearranged and reused. Despite the cheapness of rag paper and the efficiency of movable type, printing presses were costly to run and there were many in Venice which collapsed quickly. However, the industry was particularly rapid in this commercial and artistic capital; as a port city and crossroads between Europe and the world, particularly the Byzantine empire, Venice's wealth came from trade. Its wealth funded art and humanism, and the city’s prosperity allowed one hundred and fifty printing presses to be established in the final thirty years of the quattrocento. While Venice was not the first city in Italy to establish a printing industry it was the first to feel the full impact of printing. Venice was a particularly attractive city to humanists due to its abundance of Greek texts, carried west by scholars fleeing the Ottoman conquests. Aldus, whose scholarly focus was on Greek manuscripts, followed other humanists who established themselves in printing, moving to Venice in 1490 with the ambition to employ the press to provide accurate and accessible texts for students. As a well-established humanist and printer, associated with Erasmus, Manutius saw widespread popularity of the Aldine classics. Their exposure to a new generation of readers was an unintentional result of his revolution of book design, as a printer-scholar dedicated to accuracy, and with the ability to know his market, successfully weighing the publication of the popular Latin language against Greek. From 1501, italic type and the octavo format became the primary format for the spread of classical literature throughout Europe, for readers now open to the humanist message in Latin, Greek and the vernacular. The explosion of printing when it was invented reflects the thirst for knowledge and education garnered by the European population with the growth of towns, trade, and the establishment of universities during the Middle Ages.

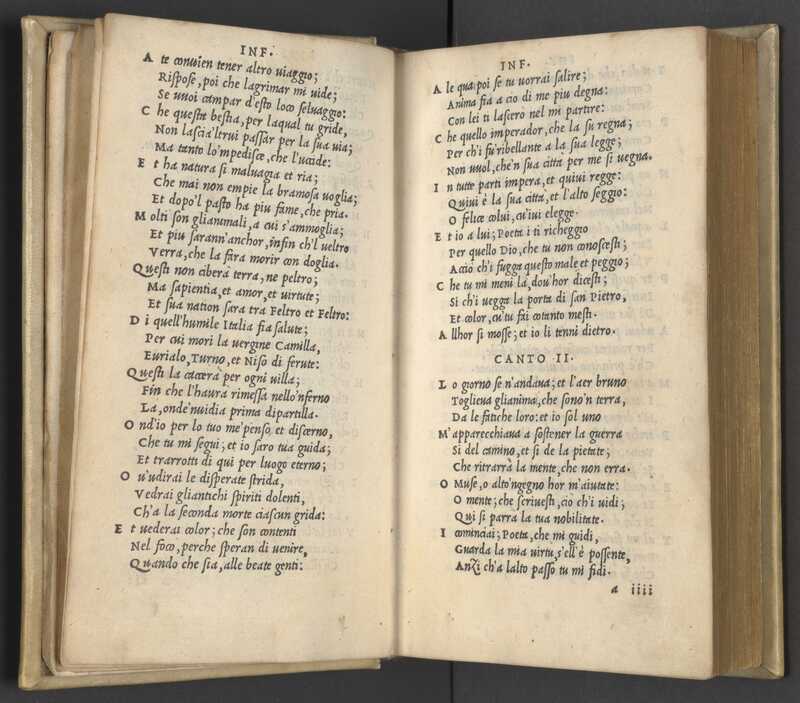

Le Terze Rime is one of three editions published by the Aldine Press in Italian, where Manutius collaborated with the editor Pietro Bembo. In printing the Florentine classics of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio, who were significant to the evolving literary consciousness, Aldus showed his faith in the future of Italian as a literary language, and in particular the Tuscan dialect. Dante Alighieri’s Commedia is a masterpieces of literature, innovative as it includes a range of content and style, featuring three line stanzas and a continuous rhyme scheme in the form of an epic poem with theological and philosophical themes. As a great medieval work it was widely circulated, and given new life by the printing press. Dante rebelled from the standard literary language of French by writing in Tuscan dialect his story of descent into Hell alongside the poet Virgil, and then their ascent to Heaven. Initially, humanists only wrote in Latin in the name of criticising medieval translations and the aristocratic culture of Italian as the elite’s language, after Petrarch’s significant separation of literature in these languages. With the growth of humanist scholarship, by the time of Manutius’ printing press at the end of the quattrocento, the vernacular saw increasing acceptance and development, partly due to patronage of scholarship by members of the elite. As a Greek scholar himself, Manutius would have been aware of the fact that Italian, like Greek, possessed both dialects and a common language, linking it to this ancient language. Manutius published Francesco Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili in 1499, a significant scholarly text on antiquity written in the vernacular; literature after this period saw a decline in classical inspiration. The subject of Dante’s work may have been relevant or interesting to humanists due to styles introduced by humanist writers who introduced, among others, comedy and satire into the vernacular. Where Dante’s work was imbued with Christian themes encompassing his classicism, humanists created a secularised literature. It is in this way that humanist books were distinctive as they embraced the new creation and format of the book through the printing press yet contents-wise, used ancient material. Furthermore, vernacular literature emerged within the humanist culture that was still defined by Latin and antiquity, continuing to influence Italian culture and academia. The works of humanists and their scholarly editions of classical Latin and Greek authors remained prevalent.

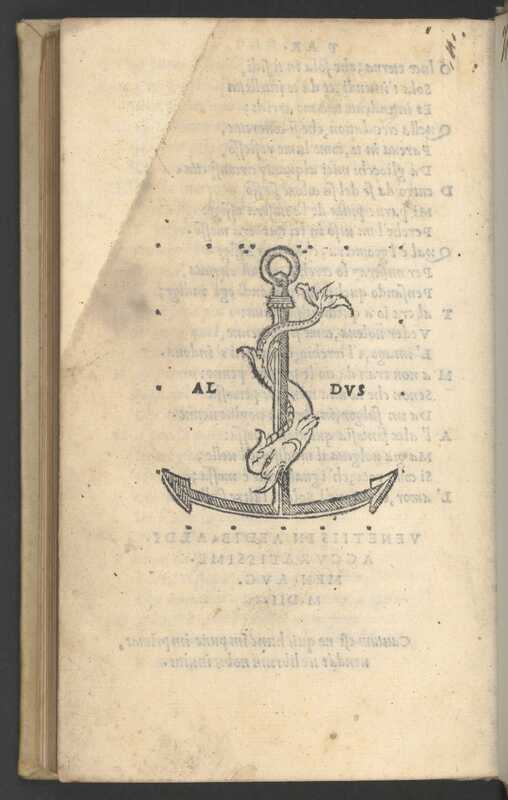

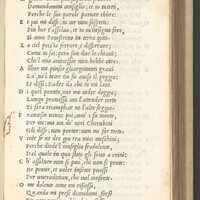

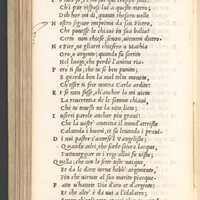

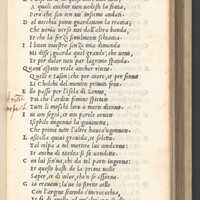

Humanists also rejected the gothic scripts of manuscripts. At the beginning of Italy’s quattrocento the humanist script arose, derived from roman script and Carolingian miniscule, which was translated into a type design for the printing press. In 1495 Manutius commissioned the typographer Francesco Griffo, who designed and cut all the Aldine fonts, although it is unsure from whose hand it derived. The type departs from the contemporary humanistic script; it is dense and sloped, and the origin of the modern-day italic. Readable and beautiful, the compactness of the font helped to save money on paper. The typeface was also so efficient and iconic that it was the model for sixteenth century French type designers of a golden age for printing in France. Matched with Manutius’ innovation of the octavo pocket format, the format and type of these books are the signature of the popular Aldine Classics. Ancestor of the modern paperback, the Octavo is a format in which a sheet is folded three times, giving eight leaves, or sixteen pages. The University of Canterbury’s copy features the Aldine device on the verso of the final leaf, whose design consists of a dolphin entwined around an anchor. Manutius adopted this design as his colophon in 1501, of which the emblem illustrates the classical motto festina lente (more haste less speed) – in this context it illustrates Manutius’ commitment to publishing meticulous editions while working on a rapid scale. The good condition of this copy attributes to this.

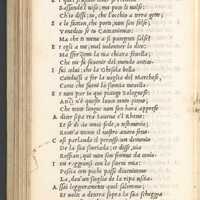

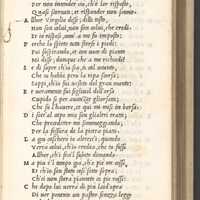

The pace of both the production and consumption of books increased, leading to greater literacy rates, greater demand and a greater ability to meet it. The press was cheap enough that within fifty years Europe contained over two hundred of them, producing more books in that short time than had been produced by hand to that point in history. Printing was not embraced with enthusiasm by all. Some noted it had the potential to perpetuate errors. Also, a handwritten book would last thousand years whereas a printed text would last a few hundred. In the central Renaissance city of Florence, the Medici considered it a degradation and initially would not allow printed books to enter their sacred libraries of manuscripts. The invention of movable type radically changed European society's access and attitude to knowledge, leading to radical changes in scholarship and religious belief. The impact on the culture of Europe may in part be attributed by the fact that print was easier to read than cursive script, enabling more efficient silent reading, and more time to think for oneself with wider access to texts. As is seen on two pages of this copy of Le Terze Rime, people privately interpreted their portable texts by writing in the margins. Despite his iconic and quality classics stamped with his iconic anchor-dolphin emblem, many printers copied his concept and despite Aldus’ commercial success he did not achieve personal wealth and died poor.

Additions:

The copy features the additions of the rare annotation and several manicules in brown ink. Unique features which show the use of the copy, still in good condition, are brown staining on the cover and fingerprint marks on the paper pages.

Notes:

With the Aldine device on the verso of the final leaf. The final line of the colophon beginning 'uendát' is indented. Several printing states exist; variation in final 2 lines of colophon. Those without the Aldine anchor and dolphin printer’s device were printed earlier, since this is one of the first ever occurrences of this device which Aldus began to use in 1502.

Physical description:

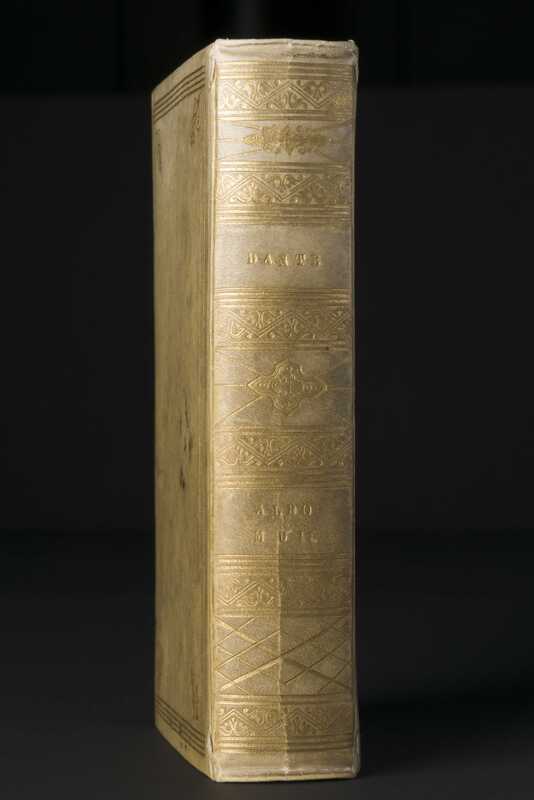

Bound in vellum, good condition, with gilt ornamentation. 18/19th century marbelling on inside cover. Spine decorated with gilt tooling and gold lettering reading DANTE/ALDO MDII.

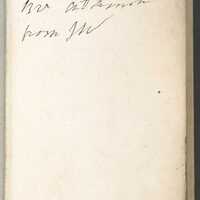

Provenance:

An armorial bookplate on the front marbled paste-down indicates that this book once belonged to James Whittle (1757-1818), a London socialite whose joint company, Laurie and Whittle, was a map and atlas publisher. His initials are also scrawled on the second page and back paste down. A second mark of the copy’s provenance is an inscription of one of its owners, Canon Carlo Barabuglini, a 19th century canon of Sant'Eustachio, contributed by Cardinale Cesare Brancadoro, a 19th century Cardinal-Priest and Archbishop. The description reads Del Can.co [Canonico] Carlo Barabuglini in attestato di sua particolare Devozione donato all’Eruditissimo suo Arcivescovo [L’] Emo [Eminentissimo] Sig.or/re Card. [Cardinale] Cesare Brancadoro. Translation: Of [belonging to/owned by] Canon Carlo Barabuglini as proof/sign of his [very] special devotion [is] gifted to his Most Learned Archbishop the Most Eminent Mr Cardinal Cesare Brancadoro.

Further reading:

- Barker, Nicola. Aldus Manutius and the Development of Greek Script & Type in the Fifteenth Century. Fordham University Press, 1985.

- Davies, Martin. “Humanism in Script and Print in the Fifteenth Century.” In The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Humanism, edited by Jill Kraye, 47–62. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Lowry, Martin. The World of Aldus Manutius: Business and Scholarship in Renaissance Venice. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1979.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid. ‘New Possibilities: Paper & Printing.’ In Reformation: Europe’s House Divided, 1490-1700, 70-76. London: Penguin, 2004.

- McLaughlin, M. L. “Humanism and Italian Literature.” In The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Humanism, edited by Jill Kraye, 224–45. Cambridge Companions to Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Pierpont Morgan Library. Art of the Printed Book, 1455-1955 : Masterpieces of Typography through Five Centuries from the Collections of the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1974.

- Trapp, J. B. “The Humanist Book.” In The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, edited by Lotte Hellinga and J. B. Trapp, 283–315. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Citing information:

Jasmine Ryan. Le terze rime. Canterbury Renaissance and Reformation, https://digitalvoyages.canterbury.ac.nz/omeka-s/s/ren_ref/page/le-terze-rime (Access date)