A leaf from the 1568 Bishop’s Bible (Report)

When Mary I who was a committed Catholic died in 1558, her Protestant half-sister, Elizabeth I , succeeded to the throne of England. Protestants, many of whom had been in exile, came back to England and encouraged Elizabeth to restore the Edwardian Protestant Church of England created by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer.

In 1559, Elizabeth sanctioned a watered-down version of that Protestantism, and parliament passed the ‘Elizabethan Settlement’. The Church of England was once again independent of the Papacy and broadly theologically Protestant, although it retained some Catholic elements. Still, as a Protestant Church, bible reading and preaching were central feature of worship and bibles in English were once again popular.

The Geneva Bible:

In 1560, a new edition of the bible in English was published in Geneva, where many Protestants had waited out Mary’s reign. Known as the ‘Marian exiles’, these clerics tended to be more radical Protestants. William Whittingham, Anthony Gilbey and other figures produced revised versions of the Old and New Testaments, published together for the first time in 1560 by Rowland Hill in Geneva.

Perhaps the most significant elements of the Geneva Bible were the annotations, marginal notes and the chapter summaries, all of which promoted a form of Protestantism that was more radical and Calvinist than the established Elizabethan Church. For this reason, it was popular with Puritans and used at home for private devotions and by preachers. Over the following decades it was used by Calvinists like John Knox and Oliver Cromwell (and republican soldiers).

The Bishops’ Bible of 1568:

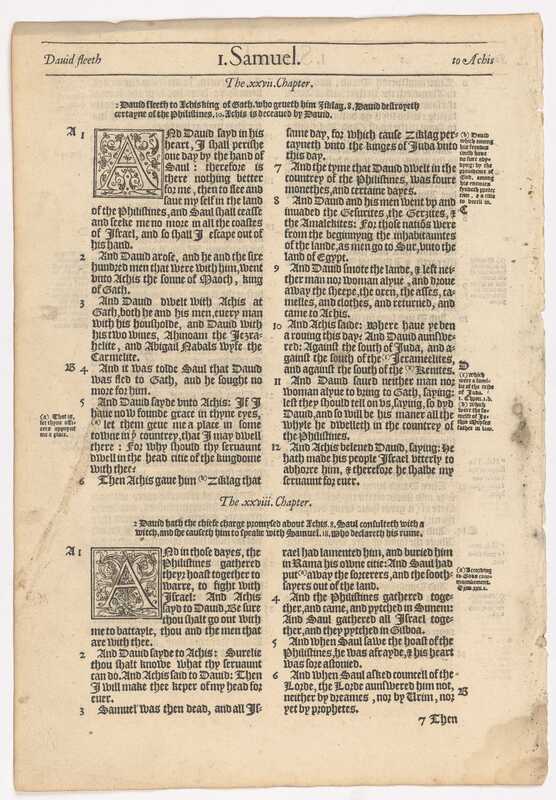

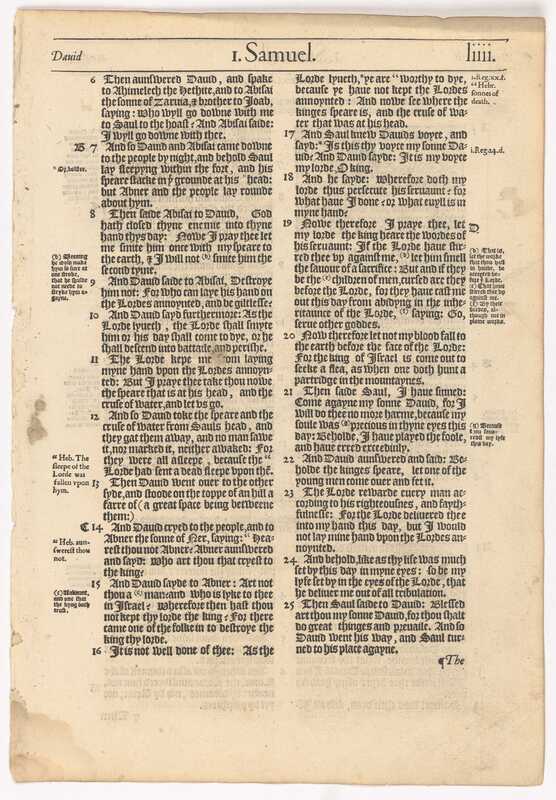

In the 1560s, the official bible in England was still the ‘Great Bible’ of 1539. While Cranmer had encouraged the licensing of the Matthew Bible, and the production of the ‘Great Bible’ his dream had been an official English edition of the Bible based on the Greek and Hebrew texts and prepared by leading clerics. This vision was taken up by Elizabeth I’s first archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker who was behind the production of this bible in 1568, commonly known as the Bishop’s Bible. By the mid-1560s, it became clear that there was an urgent need for English bibles in parish churches. The new church services of 1559 required the minister to read from the bible, and increasingly the Geneva bible, with its Calvinist interpretations, was being used. This may have been what galvanised Matthew Parker into commissioning a new official English translation. This new translation was popularly known as the Bishop’s Bible, and when it was published in 1568, the title page specified that it was ‘appointed to be read in parish churches’. This explains the size of this copy, which is a folio. It has been designed to be read from at the front of the church.

Parker commissioned a number of different clerics to do new translations of biblical texts. Rather than asking them to create entirely new translations, he asked them to follow the text of the 1539 Bible (largely based in turn on the Matthew and Tyndale versions), except where it differed significantly from the Hebrew or Greek. Some translators also drew on the 1560 Geneva translation. This ensured speed, it also meant that the influence of the older translations can be seen in the 1568 edition. Matthew Parker did many of the translations himself, including books from the Old Testament and New Testament. There were at least fifteen other translators including bishops, the dean of Westminster and theologians, but without any one person acting as editor.

Parker asked his translators to edit the bible, so that when it was read out it would be as edifying as possible. This meant cutting out parts of the text like the long genealogies in the Old Testament, to focus instead on the Christian message. Parker also told his translators to avoid ‘bitter notes upon any text’ – by this he meant the controversial glosses in the Geneva bible that were disliked by some in the Church of England. But there are many similarities between the Bishops’ Bible and the Geneva Bible (and earlier editions of the English bible). Instead of ‘bitter notes’, Parker provided explanatory introductory material at the start of each biblical book. In this he mimicked the Geneva Bible, which had long summaries as well as ‘arguments’ for chapters and books in the bible (the 1568 Bishops’ bible did not include arguments). Significantly, although the Bishops’ Bible was intended as an alternative to the Geneva bible, many of the summaries in the 1568 Bishops’ Bible echo the Genevan summaries.

There are many misprints in the 1568 Bishops’ Bible, some of which were corrected in later editions. In contrast to criticism of the editorial standards of the Bishops’ Bible, the images which accompanied the Bible have been widely praised. As well as engravings of Elizabeth I and her advisors, Robert Dudley (earl of Leicester) and William Cecil, the Bishops’ bible includes around 124 woodcut illustrations taken from books printed in Frankfurt am Main (one of them being Luther’s Bible). These woodcuts by Nuremberg artist, Virgil Solis, were bought by Archbishop Mathew Parker, and some were reworked so that God was represented by the Hebrew tetragrammaton rather than an image. By the time the new edition of the Bishops’ bible was being produced in 1572, Parker had already returned the woodblocks to Germany so he commissioned a new set of woodblocks based on the original Solis designs (including the tetragrammaton).

Despite tensions at the heart of the Elizabethan Reformation, the Bishops’ Bible continued to be printed until 1595. As well as larger, folio, editions, six quarto editions were printed between 1569 and 1584. The Bishop’s Bible has often been seen as a poor, and unsuccessful, alternative to the Geneva Bible of 1560 which has traditionally been thought of as being the culturally more significant translation. Certainly, Puritans and Calvinist Protestants (the type to read the bible extensively at home) tended to use the Geneva Bible for their household worship. However, historians have shown that while William Shakespeare used the Geneva Bible, he drew more heavily on the Bishops’ Bible. Another Elizabethan poet, Edmund Spenser, used the Bishops’ Bible, the Geneva Bible and the Great Bible of 1539. Different bibles may have been used in different settings (for example, Geneva Bibles were often printed in a smaller format than the Bishops’ Bible). And, as Lucy Wooding has argued, many people did not even read the bible in its entirety, but rather tended to read copies of just the New Testament.

References:

David J Crankshaw and Alexandra Gillespie, ‘Matthew Parker, 1504-1575’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 2004 (revised entry 2020).

Citing information:

Rosamund Oates. 'A leaf from the 1568 Bishop’s Bible'. Canterbury Renaissance and Reformation , https://digitalvoyages.canterbury.ac.nz/omeka-s/s/ren_ref/page/bishops_bible_leaf (Access date)